MY WAY-Sculpture of Chang Tzu-Lung

2017.04.28~2017.06.18

09:00 - 17:00

【INTRODUCTION】 by Wang Che-hsiong Sculptors such as Constantin Brâncuși (1876-1957), Jean Arp (1886-1966) and Henry Moore (1898-1986) were commonly fascinated with the tension of life mounting around the unaffected form of primitive art. The simplified gestalt of this

prototype” has been the lifelong artistic pursuits of Chang Tzu-Lung and the foregoing sculptors. As far as they are concerned, the so-called

essence” of sculpture refers to the sheer vitality truly existing in the gestalt of the prototype. Chang explicated this point in his statement:

The first step of transforming the representational into the abstract is to simplify the image of the human body. […] I often find many beautiful forms in human bodies, particularly in female ones that convey a soft and saturated image suggesting infinite possibilities of life. […] To provide visual focus in terms of form and achieve perfect expression in terms of connotation, I chose women’s curvy hips as the point of departure for abstraction at the beginning of simplifying my sculptural works. Since antiquity, women’s physical bodies have carried the implications of warmth, maternity, fertility and pregnancy, which is why their forms embody the attributes of dilatation and expansion, and why they fall into line with the idea about the endless stream of energy in living beings I seek to present.” Chang is probably one of the pioneering Taiwanese sculptors who deeply explore the relations between sculptural works and the base on which they stand. The sculptor tends to inscribe his name on each of his sculptural works and bases. We can tell from this responsible manner that the sculptor pays scrupulous attention to the unique qualities and expressive vocabulary of the bases’ forms and materials insofar as to treat sculptures and bases as inseparable yet mutually independent and competing units. Emulating Brâncuși and Thomas Schütte, the sculptor attempts to engage his sculptural works and their bases in meaningful dialogues, so as to make each shine more brilliantly in the others’ company. Take his newly finished sculptural work Enchantment as an example. It was made of sandstone quarried in Taiwan, carved in the form of a relatively complete woman body in a sinuous reclining position, which is different from his previous works that featured plump hips. The viewers are given a panoramic view of the curvy movement and rhythm of this figure when it is installed lower than the viewers’ eye level, which is why the sculptor insists on a flexible

coopetition layout” in terms of the sculpture-base relations. Such delicate, soft and smooth tactile qualities and curves are rarely seen in sculptural works made of sandstone quarried in Taiwan. This over-life-size nude figure appears in a version of the contrapposto position with perfectly cut limbs. It is so beautiful that gives us a visceral thrill of flamboyance, which is reminiscent of the sculptor’s statement that his creative orientation is to

transform the representational into the abstract and then reveal the representational from the abstract.” This sculptural work seems to adumbrate a new approach to this given pursuit. Made of beech though, the base of this sculptural work conveys greater warmth of humanistic naturalism. The sculptor retains the original shape of the longitudinal section of the entire piece of beech, including the grain of the sapwood, turning the beech plate into a tailor-made, comfortable mattress for the sculpture of an enchanting nude woman. The interplay between them is so intimate and harmonious even though they differ in the composing material. The sculptor’s aesthetic judgment and train of thought are coherent and seamlessly connected. Similar to Enchantment, the sculptural work Charm features a seated sandstone figure on a beech-made base with the legs arranged at slightly different levels. He adjusted the height and shape of the base by increasing the width of the beech plate in proportion to the sculpture, for the purpose of stabilizing the sculpture per se and heightening the tension of its outer edge. In this work,

simplicity” drives the sculpture and its base closer to each other. The specification of Fragrance, a piece of sculpture finished two years earlier than Charm, has clearly indicated that its rosewood-made, table-shaped base is actually part of the sculptural work. Both the sculpture and its bases are part of the entire work as well as inseparable components in terms of idea and essence. The sculptor regards Fragrance as a free-standing sculpture created with mixed media and mixed techniques. Brâncuși once claimed,

Beauty is the harmony of opposing things.” Taking advantage of the similar shades of colors, Chang managed to create a sense of harmony in the formal opposition between sculptures and bases. Harmonizing opposing shapes or colors has constituted a monumental challenge to painters, while sculptors need to be further concerned with the density and solidarity of the materials’ textures and forms. Accordingly, an artist par excellence should be able to harmonizing opposing things, which entails the abilities in mastering the visual and mental spaces. (A short excerpt from

The Dialogue between Forms and Plinths—Tzu-Lung Chang’s New Thinking about Sculpture”)

prototype” has been the lifelong artistic pursuits of Chang Tzu-Lung and the foregoing sculptors. As far as they are concerned, the so-called

essence” of sculpture refers to the sheer vitality truly existing in the gestalt of the prototype. Chang explicated this point in his statement:

The first step of transforming the representational into the abstract is to simplify the image of the human body. […] I often find many beautiful forms in human bodies, particularly in female ones that convey a soft and saturated image suggesting infinite possibilities of life. […] To provide visual focus in terms of form and achieve perfect expression in terms of connotation, I chose women’s curvy hips as the point of departure for abstraction at the beginning of simplifying my sculptural works. Since antiquity, women’s physical bodies have carried the implications of warmth, maternity, fertility and pregnancy, which is why their forms embody the attributes of dilatation and expansion, and why they fall into line with the idea about the endless stream of energy in living beings I seek to present.” Chang is probably one of the pioneering Taiwanese sculptors who deeply explore the relations between sculptural works and the base on which they stand. The sculptor tends to inscribe his name on each of his sculptural works and bases. We can tell from this responsible manner that the sculptor pays scrupulous attention to the unique qualities and expressive vocabulary of the bases’ forms and materials insofar as to treat sculptures and bases as inseparable yet mutually independent and competing units. Emulating Brâncuși and Thomas Schütte, the sculptor attempts to engage his sculptural works and their bases in meaningful dialogues, so as to make each shine more brilliantly in the others’ company. Take his newly finished sculptural work Enchantment as an example. It was made of sandstone quarried in Taiwan, carved in the form of a relatively complete woman body in a sinuous reclining position, which is different from his previous works that featured plump hips. The viewers are given a panoramic view of the curvy movement and rhythm of this figure when it is installed lower than the viewers’ eye level, which is why the sculptor insists on a flexible

coopetition layout” in terms of the sculpture-base relations. Such delicate, soft and smooth tactile qualities and curves are rarely seen in sculptural works made of sandstone quarried in Taiwan. This over-life-size nude figure appears in a version of the contrapposto position with perfectly cut limbs. It is so beautiful that gives us a visceral thrill of flamboyance, which is reminiscent of the sculptor’s statement that his creative orientation is to

transform the representational into the abstract and then reveal the representational from the abstract.” This sculptural work seems to adumbrate a new approach to this given pursuit. Made of beech though, the base of this sculptural work conveys greater warmth of humanistic naturalism. The sculptor retains the original shape of the longitudinal section of the entire piece of beech, including the grain of the sapwood, turning the beech plate into a tailor-made, comfortable mattress for the sculpture of an enchanting nude woman. The interplay between them is so intimate and harmonious even though they differ in the composing material. The sculptor’s aesthetic judgment and train of thought are coherent and seamlessly connected. Similar to Enchantment, the sculptural work Charm features a seated sandstone figure on a beech-made base with the legs arranged at slightly different levels. He adjusted the height and shape of the base by increasing the width of the beech plate in proportion to the sculpture, for the purpose of stabilizing the sculpture per se and heightening the tension of its outer edge. In this work,

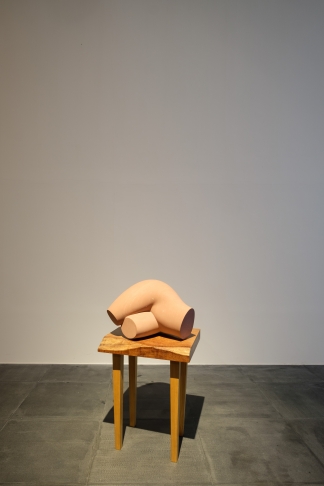

simplicity” drives the sculpture and its base closer to each other. The specification of Fragrance, a piece of sculpture finished two years earlier than Charm, has clearly indicated that its rosewood-made, table-shaped base is actually part of the sculptural work. Both the sculpture and its bases are part of the entire work as well as inseparable components in terms of idea and essence. The sculptor regards Fragrance as a free-standing sculpture created with mixed media and mixed techniques. Brâncuși once claimed,

Beauty is the harmony of opposing things.” Taking advantage of the similar shades of colors, Chang managed to create a sense of harmony in the formal opposition between sculptures and bases. Harmonizing opposing shapes or colors has constituted a monumental challenge to painters, while sculptors need to be further concerned with the density and solidarity of the materials’ textures and forms. Accordingly, an artist par excellence should be able to harmonizing opposing things, which entails the abilities in mastering the visual and mental spaces. (A short excerpt from

The Dialogue between Forms and Plinths—Tzu-Lung Chang’s New Thinking about Sculpture”)

【INTRODUCTION】 by Wang Che-hsiong Sculptors such as Constantin Brâncuși (1876-1957), Jean Arp (1886-1966) and Henry Moore (1898-1986) were commonly fascinated with the tension of life mounting around the unaffected form of primitive art. The simplified gestalt of this

prototype” has been the lifelong artistic pursuits of Chang Tzu-Lung and the foregoing sculptors. As far as they are concerned, the so-called

essence” of sculpture refers to the sheer vitality truly existing in the gestalt of the prototype. Chang explicated this point in his statement:

The first step of transforming the representational into the abstract is to simplify the image of the human body. […] I often find many beautiful forms in human bodies, particularly in female ones that convey a soft and saturated image suggesting infinite possibilities of life. […] To provide visual focus in terms of form and achieve perfect expression in terms of connotation, I chose women’s curvy hips as the point of departure for abstraction at the beginning of simplifying my sculptural works. Since antiquity, women’s physical bodies have carried the implications of warmth, maternity, fertility and pregnancy, which is why their forms embody the attributes of dilatation and expansion, and why they fall into line with the idea about the endless stream of energy in living beings I seek to present.” Chang is probably one of the pioneering Taiwanese sculptors who deeply explore the relations between sculptural works and the base on which they stand. The sculptor tends to inscribe his name on each of his sculptural works and bases. We can tell from this responsible manner that the sculptor pays scrupulous attention to the unique qualities and expressive vocabulary of the bases’ forms and materials insofar as to treat sculptures and bases as inseparable yet mutually independent and competing units. Emulating Brâncuși and Thomas Schütte, the sculptor attempts to engage his sculptural works and their bases in meaningful dialogues, so as to make each shine more brilliantly in the others’ company. Take his newly finished sculptural work Enchantment as an example. It was made of sandstone quarried in Taiwan, carved in the form of a relatively complete woman body in a sinuous reclining position, which is different from his previous works that featured plump hips. The viewers are given a panoramic view of the curvy movement and rhythm of this figure when it is installed lower than the viewers’ eye level, which is why the sculptor insists on a flexible

coopetition layout” in terms of the sculpture-base relations. Such delicate, soft and smooth tactile qualities and curves are rarely seen in sculptural works made of sandstone quarried in Taiwan. This over-life-size nude figure appears in a version of the contrapposto position with perfectly cut limbs. It is so beautiful that gives us a visceral thrill of flamboyance, which is reminiscent of the sculptor’s statement that his creative orientation is to

transform the representational into the abstract and then reveal the representational from the abstract.” This sculptural work seems to adumbrate a new approach to this given pursuit. Made of beech though, the base of this sculptural work conveys greater warmth of humanistic naturalism. The sculptor retains the original shape of the longitudinal section of the entire piece of beech, including the grain of the sapwood, turning the beech plate into a tailor-made, comfortable mattress for the sculpture of an enchanting nude woman. The interplay between them is so intimate and harmonious even though they differ in the composing material. The sculptor’s aesthetic judgment and train of thought are coherent and seamlessly connected. Similar to Enchantment, the sculptural work Charm features a seated sandstone figure on a beech-made base with the legs arranged at slightly different levels. He adjusted the height and shape of the base by increasing the width of the beech plate in proportion to the sculpture, for the purpose of stabilizing the sculpture per se and heightening the tension of its outer edge. In this work,

simplicity” drives the sculpture and its base closer to each other. The specification of Fragrance, a piece of sculpture finished two years earlier than Charm, has clearly indicated that its rosewood-made, table-shaped base is actually part of the sculptural work. Both the sculpture and its bases are part of the entire work as well as inseparable components in terms of idea and essence. The sculptor regards Fragrance as a free-standing sculpture created with mixed media and mixed techniques. Brâncuși once claimed,

Beauty is the harmony of opposing things.” Taking advantage of the similar shades of colors, Chang managed to create a sense of harmony in the formal opposition between sculptures and bases. Harmonizing opposing shapes or colors has constituted a monumental challenge to painters, while sculptors need to be further concerned with the density and solidarity of the materials’ textures and forms. Accordingly, an artist par excellence should be able to harmonizing opposing things, which entails the abilities in mastering the visual and mental spaces. (A short excerpt from

The Dialogue between Forms and Plinths—Tzu-Lung Chang’s New Thinking about Sculpture”)

prototype” has been the lifelong artistic pursuits of Chang Tzu-Lung and the foregoing sculptors. As far as they are concerned, the so-called

essence” of sculpture refers to the sheer vitality truly existing in the gestalt of the prototype. Chang explicated this point in his statement:

The first step of transforming the representational into the abstract is to simplify the image of the human body. […] I often find many beautiful forms in human bodies, particularly in female ones that convey a soft and saturated image suggesting infinite possibilities of life. […] To provide visual focus in terms of form and achieve perfect expression in terms of connotation, I chose women’s curvy hips as the point of departure for abstraction at the beginning of simplifying my sculptural works. Since antiquity, women’s physical bodies have carried the implications of warmth, maternity, fertility and pregnancy, which is why their forms embody the attributes of dilatation and expansion, and why they fall into line with the idea about the endless stream of energy in living beings I seek to present.” Chang is probably one of the pioneering Taiwanese sculptors who deeply explore the relations between sculptural works and the base on which they stand. The sculptor tends to inscribe his name on each of his sculptural works and bases. We can tell from this responsible manner that the sculptor pays scrupulous attention to the unique qualities and expressive vocabulary of the bases’ forms and materials insofar as to treat sculptures and bases as inseparable yet mutually independent and competing units. Emulating Brâncuși and Thomas Schütte, the sculptor attempts to engage his sculptural works and their bases in meaningful dialogues, so as to make each shine more brilliantly in the others’ company. Take his newly finished sculptural work Enchantment as an example. It was made of sandstone quarried in Taiwan, carved in the form of a relatively complete woman body in a sinuous reclining position, which is different from his previous works that featured plump hips. The viewers are given a panoramic view of the curvy movement and rhythm of this figure when it is installed lower than the viewers’ eye level, which is why the sculptor insists on a flexible

coopetition layout” in terms of the sculpture-base relations. Such delicate, soft and smooth tactile qualities and curves are rarely seen in sculptural works made of sandstone quarried in Taiwan. This over-life-size nude figure appears in a version of the contrapposto position with perfectly cut limbs. It is so beautiful that gives us a visceral thrill of flamboyance, which is reminiscent of the sculptor’s statement that his creative orientation is to

transform the representational into the abstract and then reveal the representational from the abstract.” This sculptural work seems to adumbrate a new approach to this given pursuit. Made of beech though, the base of this sculptural work conveys greater warmth of humanistic naturalism. The sculptor retains the original shape of the longitudinal section of the entire piece of beech, including the grain of the sapwood, turning the beech plate into a tailor-made, comfortable mattress for the sculpture of an enchanting nude woman. The interplay between them is so intimate and harmonious even though they differ in the composing material. The sculptor’s aesthetic judgment and train of thought are coherent and seamlessly connected. Similar to Enchantment, the sculptural work Charm features a seated sandstone figure on a beech-made base with the legs arranged at slightly different levels. He adjusted the height and shape of the base by increasing the width of the beech plate in proportion to the sculpture, for the purpose of stabilizing the sculpture per se and heightening the tension of its outer edge. In this work,

simplicity” drives the sculpture and its base closer to each other. The specification of Fragrance, a piece of sculpture finished two years earlier than Charm, has clearly indicated that its rosewood-made, table-shaped base is actually part of the sculptural work. Both the sculpture and its bases are part of the entire work as well as inseparable components in terms of idea and essence. The sculptor regards Fragrance as a free-standing sculpture created with mixed media and mixed techniques. Brâncuși once claimed,

Beauty is the harmony of opposing things.” Taking advantage of the similar shades of colors, Chang managed to create a sense of harmony in the formal opposition between sculptures and bases. Harmonizing opposing shapes or colors has constituted a monumental challenge to painters, while sculptors need to be further concerned with the density and solidarity of the materials’ textures and forms. Accordingly, an artist par excellence should be able to harmonizing opposing things, which entails the abilities in mastering the visual and mental spaces. (A short excerpt from

The Dialogue between Forms and Plinths—Tzu-Lung Chang’s New Thinking about Sculpture”)