Walking in the city streets, do you find the scenes familiar, or strange, to your eyes? In the shabby vendors by the road, the MRT stations late at night, or the bustling expressways and traffic around the Taipei Basin, the private emotions we feel as we are situated in the public spaces of loneliness may be diluted, followed by a unique discovery of collective sentiment.

A settlement, especially a city, is the most profound and concentrated area of human activity in the natural environment. It is also the venue where nature presents the strongest feedbacks to human society. A settlement is a product of the human race adapting and exploiting nature. It is also a place for humans to live and produce. Its form and scale are not just adaptive to the natural environment in proximity but also beneficial to production and living. Either the exterior form or assembling type of a settlement is distinctively marked by the social, economic, and geographical environments in the area.

As a simplified, alternative representation for the operational process of artifact, a “mock-up” is intended to shed light on certain parts or functions of importance in the object or process. Such mock-up often comes with parts that can be disassembled or manipulated, so that a user may disassemble or operate in line with the criteria required or purpose of analysis. Compared to a “model” that emphasizes exterior resemblance and accuracy of proportion and size, a “mock-up” stresses more on simulation of function instead of the pursuit of faithfulness on the outside.

“Scenery” refers to the visible landscape, including the terrains, fauna and flora, the natural phenomena like lightning and climates, as well as the human activities such as architecture and artificial landscapes. Nevertheless, a scenery is more than a scenery itself. A scenery is rooted in humanity. It is in the perspective of “human” that a scenery comes into being. Hence, a scenery not just is a gorgeous view, but also carries additional “meaning” in the cultural context. Without meaning, a scenery no longer presents a scenery, but merely a pile of rocks and weeds. In a nutshell, only places with human trace can be sceneries. The concept and expression of scenery are rich with cultural implications, quintessentially reflecting the profound cultural tie between mankind and their surrounding environment.

When it comes to the collective existence of artifacts in sceneries, it is difficult to overlook the discussion of “architecture”. As we approach from the styles of architecture, we will find the classical architectural styles prevalent in ancient Greece and Rome and even the Renaissance dominating people’s appreciation and attention to the appearances of architecture. There is no originality, but loyalty to standards and paradigms. Rhythmic repetition is the orthodox approach, whereas the consensus on architectural styles becomes the foundation for landscape aesthetics. Not until the end of the 19th century was the obsession in the pursuit of a consensus in architectural aesthetics replaced by the emergence of “engineers” advocating scientific standards.

The function-based stance filled the people with hopes for “the future”. The notion of modernism dominated by engineer’s perspective claimed to have found the ultimate solution to the unresolved quarrel over architectural aesthetics – the point of architecture is not for beauty, but for the purposes it serves. The seemingly decisive turn is in fact nothing but the introduction of a value to replace the predecessor. The architects (or engineers) of modernism stand the same with those architects before them, seeking to communicate certain messages with their architecture. Nonetheless, what the modernists aim to communicate no longer is the aesthetics in the old days, nor is it the attitude toward life in the Middle Age or ancient Rome or Greece. What they attempt to communicate via architecture is the “visions for the future” of the times, including the imaginations for technology, speed, democracy, and science.

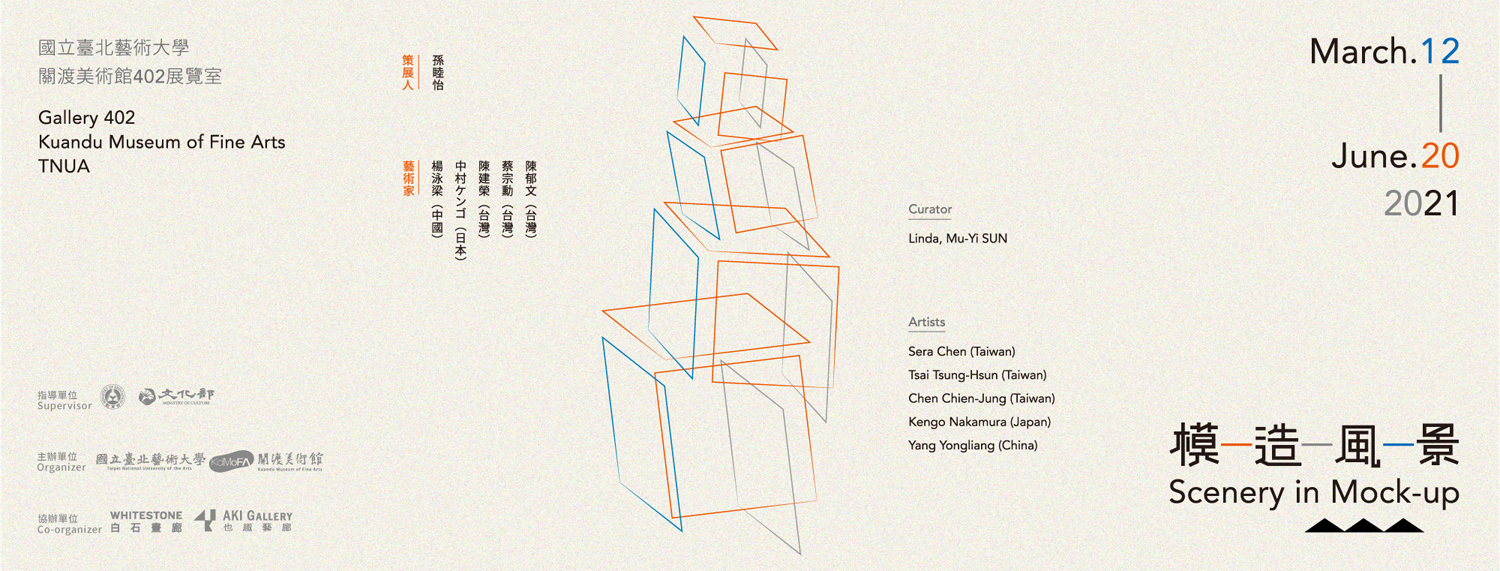

It starts with Landscape 129 by Chen Chien-Jung in this exhibition, the seemingly flipping of the architecture schematics of Le Corbusier (1887-1965), a maestro of modern architecture. Aiming at flatting the 3D architecture, along with partial blurring on the surface, the expressionist suspends the consciousness of bridging the ideal architecture with everyday life, serving as the initiation for Scenery in Mock-up. Kengo Nakamura employs the classic squares of color red, yellow, blue, and black of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) to illustrate the floor plan of studio apartment in Tokyo, introducing the contemporary spatial lexicon in the classical visual experiences. Yang Yongliang’s digital landscapes are developed on the basis of the recorded imageries of concrete urban scenes and manmade machineries. With post-editing and montage techniques, the mimicked scenes of landscape painting in the Sung Dynasty of China develop into the bustling traffic of the past, misplaced and flowing in modern times. As we revisit Chen Chien-Jung’s Landscape series, the paired works of spatial perspective steer the flow of viewing perspective with the traditional painting techniques, while the inverted sense of space baffles our visual inertia. Communicating the geometrical order of architectural building, it also reconfigures the order of artificial imageries and enquires the relationship of spatial scenery with form and structure in return. In addition, Tsai Tsung-Hsun’s videos facilitate our thinking via the promotional approaches familiar in the commoner’s life. Whereas we pursue certain things, lured by its attempt to bend our view in favor of specific goal or perspective, is it a cleansing of our value or an alternative imagination toward a good life such promotional approach aims to introduce to us? Finally, Sera Chen’s The Habitat on The Skyline utilizes the add-on landscape in day and night, searching for the awareness reminder of architectural form under the social fabric.

Scenery in Mock-up endeavors to present interpretations and experiences of the contemporary aesthetics, culture, and society of humanity and nature. The artistic presentation and interpretation of scenery progress with times. Where there is “human”, there is space and place to accommodate, produce, and reproduce (mock-up) its meaning. This exhibition ponders over the mock-up realities of cultural/artificial landscapes in the propositions of artificial nature, architectural lexicon, structural disassociation, and post-editing processing, so as to evoke viewer’s visual perception and reasoning logic.