Journey to Natural Path

2008.12.05~2009.02.08

09:00 - 17:00

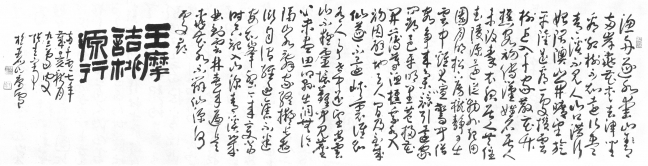

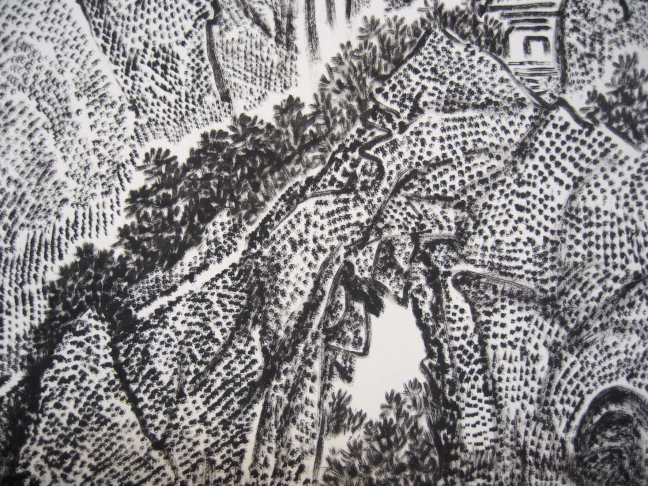

By Chao Yu-Hsiu Due to the rapid transformative attitudes toward contemporary art styles, performative connotation, expression and taste in the external environment, Chinese calligraphy and painting relatively decline. Technology has accelerated the transformation of life style. The acculturation differs from generation to generation. New ideas have been created within shorter intervals while the gaps between individual’s aesthetic perceptions get widened. As a result, the alternation in art is hastened. The impermanent subordinate Chinese calligraphy and painting thus, under the trend of cross-transgression, might need to retrieve public attraction with renewed content. From another perspective, the informative explosion misleads us that life is a series of constant accumulation, download and update. The earth also suffers from bottomless human desires causing the destruction accompanying with technological convenience. Stop deprive the earth of its natural resources at will might be our priority, but the fundamental mission is to retrospect toward one’s inner self. Therefore, what one should ponder in his daily life, anytime anywhere, is to overlook the nature of life, insight of being merged with the sky and the ground as well as the philosophy of less diligence in life. The idea of all-in-one has long been embedded into the substance of the aesthetics in Chinese calligraphy and painting with pavement of the philosophy in pre-Chin period. In art performance, it still holds the value of incidental exploration and constant preservation. People who keep their cultural conscience and mission in mind resort to all kinds of exhibitive themes and methods to rescue Chinese calligraphy and painting out of its current plight. They attempt to provide the artists ways to introspect their own standings and inject vitality with the latest opinions to strike the deep core of contemporary aesthetics. That might lead us to a new door. Professor Chang Kuang-Pin is one of these prominent barriers of Chinese calligraphy and paintings. He has spent almost a century in studying, creating and teaching, the 94-year-old professor still move forward in his settlement in Chinese calligraphy and painting. His insights in life and open-minded attitude are all reflected in his pursuit of line, texture and metaphors. Very much different from that of most modern artists who stress to represent partial visual world, his works always try to cast lights upon his admiration toward landscapes in calligraphy and painting. The arrangement of his creativity is far more beyond what people who indulge themselves within delicate art skills could dream of. He applies rich ink stroke with cursive and seal characters to lineate the landscapes and express his mood of casual admiration with detached interest. Not only his painting skill corresponds to his calligraphical works, but they have already become one. Since he turned 87 years old, he has constantly surprised his audience with master pieces, and his sophisticated arrangement in cursive calligraphy has united the boundary between hook-drop and stamp sign. At the age of 91, he has developed the rich-ink-drop-wrinkle-draw and then provided a more experienced figure of the mountains in his works. Besides, he enlarges the size of his works with freestyle long volumes, and has become one of the most original and magnificent masters. When National College of Fine Art, which has later become current Taipei National University of Arts, was established in 1982, professor Kuang-Pin was introduced by professor Huai-Shuo to take charge of calligraphical courses and thus got close to a group of calligraphy-loving students. The amount of his assignments and production was astonishingly large. In addition to rice paper painting, he had also practiced on all sorts of books and cards. The complexity and devotion in his work might not be next to those in the ancient classics, but he always gave away his works generously. This sixty-turning artist had prepared himself for all requirement. His personal characteristic with casual but solid cursive calligraphy has already been indistinctly fermented within his drawings. If the time allows, he might be a slowly matured star. Since his retirement from National Palace Museum in 1987, he has devoted himself into painting and calligraphy. He has hold art exhibitions for many times, and each has brought something new to the audience. But he has still maintained his mood for fun, for change. At the age of 94, he is still very healthy, both physically and spiritually. Therefore he keeps creating works on long banners or volumes, and the large size books are not rare either. In his latest collection, the nicknamed “shark fin wrinkle” skill wanders around odd figures regardless of traditional art expression. The “shark fin wrinkle” has overturned our fixed definition that wrinkle must be the calligraphical application on mimicking the lines of stones and trees. But the renovation makes it much easier for the audience to realize the artist's childishness, while his dropping and stamping, as well as the fun of traditional calligraphy. Perhaps on the angle of creativity, the artist should ground his basis upon playfulness-a game play with brush, ink, paper and water. While “playing,” one would recognize the uniqueness of each items and the inter-relationship among them. Furthermore, to create one’s own tricks from the old rules and break them in turn. That’s where the originality occurs. If one was limited with the old rules, no revolution could be made. When Shi-Tao declared that “brush and ink go with time”, he means nothing more than the liberal attitude. That is exactly what professor Kuang-Pin carries out. Instead of pursuing some dazzling success, or presuming a far far ideal, he resorts to find his own way to play unrestrictedly, spontaneously and insistently. As for now, in his terms, “he has found his way to play freely,” which might sounds childlike but comes from a 94-year-old man. He’s research, promotion and production on cursive calligraphy has made him the most successful calligraphical artist since the “standard cursive calligraphy” leader Yu You-Ren. To facilitate the younger learners to identify the structure of cursive calligraphy, he has concluded a 26-entry formula with the inspiration from two sentences pronounced in Chui Yuan’s work “Cursive Style”- “to constrain on the left side and lift on the right side” as well as “to make circle without the compass and to draw square without the frame.” To go further, the conventional way of calligraphy learning always starts with “Seventeen Copybooks,” “Thousand Words in Cursive Calligraphy,” and “Copybook of Books,” those of which are not only limited in the number of vocabulary, but also lack circulation in content and consequently retard the beginners and leave them with the impression of distance. To help the future learner, professor Kuang-Pin has transcribed well-known Chinese classics, including “Three-Hundred Collection of Tang Poetry,” “Three-Hundred Collection of Song Proses,” “The Tale of Vegetable Roots,” “Ballad Collection of Su Dong-Po,” “The Classics of the Virtue of the Tao,” and the “Collection of Tao Yuan-Ming,” in cursive calligraphy. No need to say that his painstaking contribution will be the easiest shortcut of future cursive calligraphy education and leave extraordinary impact on the descendents. Chinese old saying “calligraphy is the painting by inner spirit,” might sound cliché, but it did stress out the fact that the artist's taste and mood would indirectly influence the reflection of inner motion through the drawing and affect the audience. The calligraphical transformation should correspond to the ideal life rhythm, in other words, the rhythm of nature, of vitality, of self-cultivation consistent with the virtue of Tao. And its calligraphical expression should come from one’s deep core spontaneously. It could be controllably powerful and yet constraint and harmonious at the same time. Huang Bin-Hong used to make such comment on painting; “Some paintings are astonished at the first sight but turns out to be boring within short time. Those are the worst works. Some are good at the beginning, and still attract their audience. Those are good works. And some are not so well-received at the very start, but their hidden values are discovered as time goes by and only audience with the intelligence could tell. The key point lies in the way of using the brush. Those are the classics.” As a matter of fact, this critic bases primarily on the technique of drawing; therefore, it also applies to calligraphy. The best calligraphical works are often “not so well received at the very start, but their hidden value discovered as time goes by and only audience with the intelligence could tell.” Professor Kuang-Pin has used to write with long writing brush made of goat’s hair, and stayed with medium round stroke. His latest works are tenderly raised and pressed with the fusion of rough seal characters and wild cursive thus create an appearance of stone rubbing style but an exclusive engraving charm inside. He has conducted the writing brush as pliable whip to carve into the surface of the stone. The left track seems soft but solid, fluent and yet tough. Overall speaking, sometimes he bursts through the lines, seemingly confused but follows invisible regulation. Sometimes he stops suddenly, but the spirit has already shown. Whether being running or stopped, he writes fluently, both peaceful and clear. Dry ink with vacant magic. The longer one looks at his work the more he learns the degree of difficulty to dig out the mystery hidden. Some artists reach their peak at young age while some occasionally achieve good pieces after mid-life. There are also some maintain their impetus in art, though get rid of secular burden, but their lives are not long enough to retrieve another peak, for instance, Fu Bao-Shi. The most subtle cases are those who have accomplished or dramatically changed at their later part of life. Both the artists and the works are entering anther maturity. The skill is neglected but improved, while the content is released from turning back to the prime nature. As a result, their works are beyond description. Huang Bin-Hong, Qi Bai-Shi and Yu Cheng-Vao are typical cases. So is professor Kuang-Pin that stands at the full rim of his rich life. He's not only contributed in art but also proved the chance by time. This collection includes the volumes of “Cursive Three-Hundred Tang Poetry”, that took professor Kuang-Pin 6 months to finish at the age of 93, along with the latest rich ink landscape painting pieces. If we try to follow what professor Kuang-Pin always says, “slow down, take it easy,” and hold this attitude to take full time to see through his works, we might be able to find out that each drop and stoke in his works demonstrate a view of life- “freedom.”

By Chao Yu-Hsiu Due to the rapid transformative attitudes toward contemporary art styles, performative connotation, expression and taste in the external environment, Chinese calligraphy and painting relatively decline. Technology has accelerated the transformation of life style. The acculturation differs from generation to generation. New ideas have been created within shorter intervals while the gaps between individual’s aesthetic perceptions get widened. As a result, the alternation in art is hastened. The impermanent subordinate Chinese calligraphy and painting thus, under the trend of cross-transgression, might need to retrieve public attraction with renewed content. From another perspective, the informative explosion misleads us that life is a series of constant accumulation, download and update. The earth also suffers from bottomless human desires causing the destruction accompanying with technological convenience. Stop deprive the earth of its natural resources at will might be our priority, but the fundamental mission is to retrospect toward one’s inner self. Therefore, what one should ponder in his daily life, anytime anywhere, is to overlook the nature of life, insight of being merged with the sky and the ground as well as the philosophy of less diligence in life. The idea of all-in-one has long been embedded into the substance of the aesthetics in Chinese calligraphy and painting with pavement of the philosophy in pre-Chin period. In art performance, it still holds the value of incidental exploration and constant preservation. People who keep their cultural conscience and mission in mind resort to all kinds of exhibitive themes and methods to rescue Chinese calligraphy and painting out of its current plight. They attempt to provide the artists ways to introspect their own standings and inject vitality with the latest opinions to strike the deep core of contemporary aesthetics. That might lead us to a new door. Professor Chang Kuang-Pin is one of these prominent barriers of Chinese calligraphy and paintings. He has spent almost a century in studying, creating and teaching, the 94-year-old professor still move forward in his settlement in Chinese calligraphy and painting. His insights in life and open-minded attitude are all reflected in his pursuit of line, texture and metaphors. Very much different from that of most modern artists who stress to represent partial visual world, his works always try to cast lights upon his admiration toward landscapes in calligraphy and painting. The arrangement of his creativity is far more beyond what people who indulge themselves within delicate art skills could dream of. He applies rich ink stroke with cursive and seal characters to lineate the landscapes and express his mood of casual admiration with detached interest. Not only his painting skill corresponds to his calligraphical works, but they have already become one. Since he turned 87 years old, he has constantly surprised his audience with master pieces, and his sophisticated arrangement in cursive calligraphy has united the boundary between hook-drop and stamp sign. At the age of 91, he has developed the rich-ink-drop-wrinkle-draw and then provided a more experienced figure of the mountains in his works. Besides, he enlarges the size of his works with freestyle long volumes, and has become one of the most original and magnificent masters. When National College of Fine Art, which has later become current Taipei National University of Arts, was established in 1982, professor Kuang-Pin was introduced by professor Huai-Shuo to take charge of calligraphical courses and thus got close to a group of calligraphy-loving students. The amount of his assignments and production was astonishingly large. In addition to rice paper painting, he had also practiced on all sorts of books and cards. The complexity and devotion in his work might not be next to those in the ancient classics, but he always gave away his works generously. This sixty-turning artist had prepared himself for all requirement. His personal characteristic with casual but solid cursive calligraphy has already been indistinctly fermented within his drawings. If the time allows, he might be a slowly matured star. Since his retirement from National Palace Museum in 1987, he has devoted himself into painting and calligraphy. He has hold art exhibitions for many times, and each has brought something new to the audience. But he has still maintained his mood for fun, for change. At the age of 94, he is still very healthy, both physically and spiritually. Therefore he keeps creating works on long banners or volumes, and the large size books are not rare either. In his latest collection, the nicknamed “shark fin wrinkle” skill wanders around odd figures regardless of traditional art expression. The “shark fin wrinkle” has overturned our fixed definition that wrinkle must be the calligraphical application on mimicking the lines of stones and trees. But the renovation makes it much easier for the audience to realize the artist's childishness, while his dropping and stamping, as well as the fun of traditional calligraphy. Perhaps on the angle of creativity, the artist should ground his basis upon playfulness-a game play with brush, ink, paper and water. While “playing,” one would recognize the uniqueness of each items and the inter-relationship among them. Furthermore, to create one’s own tricks from the old rules and break them in turn. That’s where the originality occurs. If one was limited with the old rules, no revolution could be made. When Shi-Tao declared that “brush and ink go with time”, he means nothing more than the liberal attitude. That is exactly what professor Kuang-Pin carries out. Instead of pursuing some dazzling success, or presuming a far far ideal, he resorts to find his own way to play unrestrictedly, spontaneously and insistently. As for now, in his terms, “he has found his way to play freely,” which might sounds childlike but comes from a 94-year-old man. He’s research, promotion and production on cursive calligraphy has made him the most successful calligraphical artist since the “standard cursive calligraphy” leader Yu You-Ren. To facilitate the younger learners to identify the structure of cursive calligraphy, he has concluded a 26-entry formula with the inspiration from two sentences pronounced in Chui Yuan’s work “Cursive Style”- “to constrain on the left side and lift on the right side” as well as “to make circle without the compass and to draw square without the frame.” To go further, the conventional way of calligraphy learning always starts with “Seventeen Copybooks,” “Thousand Words in Cursive Calligraphy,” and “Copybook of Books,” those of which are not only limited in the number of vocabulary, but also lack circulation in content and consequently retard the beginners and leave them with the impression of distance. To help the future learner, professor Kuang-Pin has transcribed well-known Chinese classics, including “Three-Hundred Collection of Tang Poetry,” “Three-Hundred Collection of Song Proses,” “The Tale of Vegetable Roots,” “Ballad Collection of Su Dong-Po,” “The Classics of the Virtue of the Tao,” and the “Collection of Tao Yuan-Ming,” in cursive calligraphy. No need to say that his painstaking contribution will be the easiest shortcut of future cursive calligraphy education and leave extraordinary impact on the descendents. Chinese old saying “calligraphy is the painting by inner spirit,” might sound cliché, but it did stress out the fact that the artist's taste and mood would indirectly influence the reflection of inner motion through the drawing and affect the audience. The calligraphical transformation should correspond to the ideal life rhythm, in other words, the rhythm of nature, of vitality, of self-cultivation consistent with the virtue of Tao. And its calligraphical expression should come from one’s deep core spontaneously. It could be controllably powerful and yet constraint and harmonious at the same time. Huang Bin-Hong used to make such comment on painting; “Some paintings are astonished at the first sight but turns out to be boring within short time. Those are the worst works. Some are good at the beginning, and still attract their audience. Those are good works. And some are not so well-received at the very start, but their hidden values are discovered as time goes by and only audience with the intelligence could tell. The key point lies in the way of using the brush. Those are the classics.” As a matter of fact, this critic bases primarily on the technique of drawing; therefore, it also applies to calligraphy. The best calligraphical works are often “not so well received at the very start, but their hidden value discovered as time goes by and only audience with the intelligence could tell.” Professor Kuang-Pin has used to write with long writing brush made of goat’s hair, and stayed with medium round stroke. His latest works are tenderly raised and pressed with the fusion of rough seal characters and wild cursive thus create an appearance of stone rubbing style but an exclusive engraving charm inside. He has conducted the writing brush as pliable whip to carve into the surface of the stone. The left track seems soft but solid, fluent and yet tough. Overall speaking, sometimes he bursts through the lines, seemingly confused but follows invisible regulation. Sometimes he stops suddenly, but the spirit has already shown. Whether being running or stopped, he writes fluently, both peaceful and clear. Dry ink with vacant magic. The longer one looks at his work the more he learns the degree of difficulty to dig out the mystery hidden. Some artists reach their peak at young age while some occasionally achieve good pieces after mid-life. There are also some maintain their impetus in art, though get rid of secular burden, but their lives are not long enough to retrieve another peak, for instance, Fu Bao-Shi. The most subtle cases are those who have accomplished or dramatically changed at their later part of life. Both the artists and the works are entering anther maturity. The skill is neglected but improved, while the content is released from turning back to the prime nature. As a result, their works are beyond description. Huang Bin-Hong, Qi Bai-Shi and Yu Cheng-Vao are typical cases. So is professor Kuang-Pin that stands at the full rim of his rich life. He's not only contributed in art but also proved the chance by time. This collection includes the volumes of “Cursive Three-Hundred Tang Poetry”, that took professor Kuang-Pin 6 months to finish at the age of 93, along with the latest rich ink landscape painting pieces. If we try to follow what professor Kuang-Pin always says, “slow down, take it easy,” and hold this attitude to take full time to see through his works, we might be able to find out that each drop and stoke in his works demonstrate a view of life- “freedom.”