Wandering in the poetry

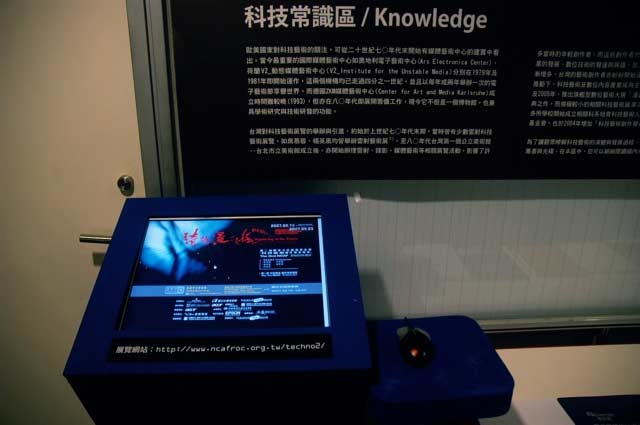

2007.11.30~2008.01.13

09:00 - 17:00

About this Exhibition Wandering in the Poetry: the 2nd NCAF Techno Art Creation Project presents this year’s five awardees. NCAF’s intent is to develop the entire visual arts field by encouraging talented domestic artists working with new technology and continue promoting technology art through collaborations between NCAF and the Taiwanese businesses that support the Techno Art Creation Project grant. While riding the current wave of technology art in Taiwan, and facing the pride or controversy that this has created, is there still a special or secret way for us to return to the original intent of art without losing its essential pursuit? This year’s five awardees—Tsai Wan-Shuen, Chang Po-Chih, Lin Jiun-Ting, Lin Chi-Wei and Wu Chi-Tsung—pursue their individual artistic concepts by utilizing and combining different technological media, equipment and software to present images, spaces and atmospheres that are each like modern technological poems. The fascinating content and interactive nature of each work draw the audience into the artist’s poetic environment, which contains stories, scenery, dreamscapes, deja vu or other visual phenomena. New media art is both futuristic and poetic, and in the same way that poetry is the crystallization of language, new media art embodies the spirit of contemporary art and affords the possibility of poetic wandering.

About this Exhibition Wandering in the Poetry: the 2nd NCAF Techno Art Creation Project presents this year’s five awardees. NCAF’s intent is to develop the entire visual arts field by encouraging talented domestic artists working with new technology and continue promoting technology art through collaborations between NCAF and the Taiwanese businesses that support the Techno Art Creation Project grant. While riding the current wave of technology art in Taiwan, and facing the pride or controversy that this has created, is there still a special or secret way for us to return to the original intent of art without losing its essential pursuit? This year’s five awardees—Tsai Wan-Shuen, Chang Po-Chih, Lin Jiun-Ting, Lin Chi-Wei and Wu Chi-Tsung—pursue their individual artistic concepts by utilizing and combining different technological media, equipment and software to present images, spaces and atmospheres that are each like modern technological poems. The fascinating content and interactive nature of each work draw the audience into the artist’s poetic environment, which contains stories, scenery, dreamscapes, deja vu or other visual phenomena. New media art is both futuristic and poetic, and in the same way that poetry is the crystallization of language, new media art embodies the spirit of contemporary art and affords the possibility of poetic wandering.

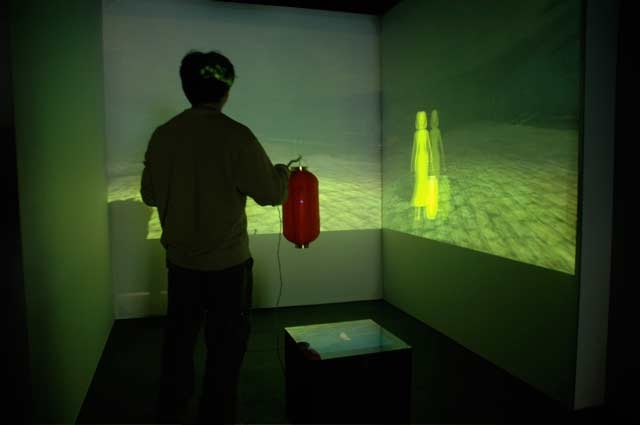

Dr. Ava Hsueh / Director of National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts “At the intersection of art and technology, we see ambiguous light and images, an engagement neither friendly nor aloof; it can be a simple statement or an audacious catharsis, or a tireless rant, sometimes hidden and sometimes apparent, sometimes hastened and sometimes suspended, or provocative, but always able to ravish the soul like poetry.” Art is the collective record of human experience, and along with the changes of the times, technological progress has rewritten the features of human life and greatly influenced the evolution of civilization. Inevitably, science and technology have become creative media for artists. Although technology has prove n to be a breakthrough artistic form, the coupling of art and technology is like a painter using a paintbrush to explain life, a musician playing the sounds of heaven on a musical instrument or the same as dancers using their bodies to demonstrate capabilities. Because of this, technology-based art can be a way of experiencing, a kind of annotation, a pivot, or magic that links extremes. Contemporary artists have brought technology into the palace hall of art, opening up the traditionally acknowledged category of aesthetics, and also urging forward the pluralization of the artistic forms. After the 1990s, wave after wave of digital art activities brought the viewing public into contact with boundless possibilities which transcended time and space. While surfing the Internet, one can receive and disseminate every kind of information. This kind of technology-based art compresses the distance between people, and presents a composite reality in the space between the virtual and actual worlds. Even more, while engaged in an interactive process, multiple sparks are ignited and reverberations are set off. Wandering in Poetry: the 2nd NCAF Techno Art Creation Project exhibits the work of five artists—Tsai Wan-Shuen, Chang Po-Chih, Lin Jiun-Ting, Lin Chi-Wei and Wu Chi-Tsung—who have set out from their personal experiences and utilize different technology-based media to create astounding work which comments on a rich assortment topics. As artist Lin Chi-Wei explains in his own words: “I eliminate music theory, musical instruments, orchestras and all kinds of musical systems and return music back to a time of pre-civilization, when divisions between humanity and animals didn’t exist, in order to reply to the wailing instinct within our flesh. Tsai Wan-Shuen explains ” Lin Jiun-Ting says, “I explore the physical perceptions of the audience as they walk through interactive projected images. In this way I take lower levels of awareness and make them into surface layers and this becomes the audience's experience of reality.”her work as follows: “Using possibilities created by multimedia technology and combining my subjective choices with accidents, I produce a video environment for the audience as they roam about…” The marvels and magnificence of technology-based art have emerged along with the projected image, which, besides dazzling our eyes and ears, contains poetic significance and emanates artistic enchantment. The value of art rests in the varied backgrounds of its beholders. We all analyze and appreciate art from different perspectives, and the stimulation of such an innate experience can be explained in many different ways. This process in turn expands the definition of art and this is exactly what this exhibition intends to do.

Dr. Ava Hsueh / Director of National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts “At the intersection of art and technology, we see ambiguous light and images, an engagement neither friendly nor aloof; it can be a simple statement or an audacious catharsis, or a tireless rant, sometimes hidden and sometimes apparent, sometimes hastened and sometimes suspended, or provocative, but always able to ravish the soul like poetry.” Art is the collective record of human experience, and along with the changes of the times, technological progress has rewritten the features of human life and greatly influenced the evolution of civilization. Inevitably, science and technology have become creative media for artists. Although technology has prove n to be a breakthrough artistic form, the coupling of art and technology is like a painter using a paintbrush to explain life, a musician playing the sounds of heaven on a musical instrument or the same as dancers using their bodies to demonstrate capabilities. Because of this, technology-based art can be a way of experiencing, a kind of annotation, a pivot, or magic that links extremes. Contemporary artists have brought technology into the palace hall of art, opening up the traditionally acknowledged category of aesthetics, and also urging forward the pluralization of the artistic forms. After the 1990s, wave after wave of digital art activities brought the viewing public into contact with boundless possibilities which transcended time and space. While surfing the Internet, one can receive and disseminate every kind of information. This kind of technology-based art compresses the distance between people, and presents a composite reality in the space between the virtual and actual worlds. Even more, while engaged in an interactive process, multiple sparks are ignited and reverberations are set off. Wandering in Poetry: the 2nd NCAF Techno Art Creation Project exhibits the work of five artists—Tsai Wan-Shuen, Chang Po-Chih, Lin Jiun-Ting, Lin Chi-Wei and Wu Chi-Tsung—who have set out from their personal experiences and utilize different technology-based media to create astounding work which comments on a rich assortment topics. As artist Lin Chi-Wei explains in his own words: “I eliminate music theory, musical instruments, orchestras and all kinds of musical systems and return music back to a time of pre-civilization, when divisions between humanity and animals didn’t exist, in order to reply to the wailing instinct within our flesh. Tsai Wan-Shuen explains ” Lin Jiun-Ting says, “I explore the physical perceptions of the audience as they walk through interactive projected images. In this way I take lower levels of awareness and make them into surface layers and this becomes the audience's experience of reality.”her work as follows: “Using possibilities created by multimedia technology and combining my subjective choices with accidents, I produce a video environment for the audience as they roam about…” The marvels and magnificence of technology-based art have emerged along with the projected image, which, besides dazzling our eyes and ears, contains poetic significance and emanates artistic enchantment. The value of art rests in the varied backgrounds of its beholders. We all analyze and appreciate art from different perspectives, and the stimulation of such an innate experience can be explained in many different ways. This process in turn expands the definition of art and this is exactly what this exhibition intends to do.

J J Shih, Director of Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts at Taipei National University of the Arts Fermenting Poetry from Technology—Preface Taiwan’s national hope of developing into tomorrow’s island of technology lies in its people’s acceptance and use of technological products, and it could be said that both technological equipment and software are considerably commonplace. Mobile phones, every household equipped with a computer, online shopping and searching for information and using email to communicate: these are just some obvious examples among many of the rampant spread of technology. Culture and the arts are even undergoing unavoidable, qualitative and quantitative change. Most obviously, with technology backing new media artists their numbers are increasing daily, as are related exhibitions. It is undeniable that technology-based art has become the unavoidable fashion of our times, but even more important than the creation of transformations in creative media and technology, is the substantial expansion in creative thinking and space for imagination created by new technologies, and also the ways we appreciate and experience art. On the international stage of contemporary art, techno art is already considered a celebrated theory and never-ending source of power, and in Taiwan, it has completely captured the attention of younger generation artists and become a creative choice in high demand. Currently, although the work of domestic technology-based artists has just begun and the numbers involved are still few, there are several Taiwanese artists who have captured the attention and received affirmation on the international stage, and this has inspired even greater numbers to join in. Looking around Taiwan, many initiatives spurring on technology-based art have taken shape. Not only are many universities offering art education courses, but they are also including techno art as a formal course of study. Additionally, studios have been established for research and development, businesses are funding foundations and the government has instituted policies that allocate grants for the creative technology industry. As early as three years ago, thanks to the support of the domestic technology industry and their identification with this project, the Techo Art Creation Project segment of the granting program at the National Culture and Arts Foundation was set forth. This all has been clearly explained; Taiwan, island of technology, has all it takes in terms of resources, talent, recognition and technology to sustain promotion and development of future forms of technology-based art, but perhaps what we require is more effective initiative and better integrated systems. Technology has gradually changed our everyday habits, as well as our values and ways of thinking. However, these aren’t necessarily all positive changes. Everyday, we see first hand and hear stories of how technology has led individuals astray and created a multitude of social problems. Truly, this we should acknowledge: there is no way possible for technology-based art to be a panacea for all art or become the sole wave of the future. Currently, the general public has confirmed that technology-based art has created numerous possibilities and opened completely new horizons, yet there are many critics who have raised warnings in succession—this spectacular wave of interactivity in techno art may gradually lead art to amusement for the masses, greatly reducing art’s ideological connotation and humanistic depth. To be fair, techno art has indeed launched a new era in artistic perception, but where the value and significance of this new era is heading remains stuck in a vast and hazy phase, abetted by the theorists’ inability to articulate comprehensive themes. In the creative camp, discourses tend to focus on new approaches for technology-based art and a return to art's essence. It cannot be denied, this is a question that every artist working with new technology must ask him or herself, and then find an answer. Considering the degree to which technology has been assimilated into the daily life of Taiwan, techno art is still a very fresh and difficult to fathom term. Therefore, Taiwan has a long way to go before it can answer Mr. Stan Shih’s call, and advance from being the island of technology to the island of cultural technology, and even take the lead as the techno art island. This year, the National Culture and Arts Foundation, with the assistance of contributions from private businesses, has awarded grants to artists working with new technology; mounted a traveling exhibition at museums in northern, central and southern Taiwan to introduce new achievements in the field of technology-based art to the public and organized a teacher training camp along with a course of techno-art related lectures. It is the hope of everyone involved that this programming, under the guidance of NCAF, will yield many possibilities for the future of the arts and provide the people of Taiwan with an enjoyable and enriching experience. This year’s honors have been bestowed upon five artists: Tsai Wan-Shuen, Chang Po-Chih, Lin Jiun-Ting, Lin Chi-Wei and Wu Chi-Tsung. Each artist uses new media differently to carefully express their individual concepts, aesthetic inclinations and interpretation of culture. The collected works of these five artists, besides exhibiting the multiple faces of technology-based art in Taiwan, also reflect the investigative attention to multiple layers of significance by local artists in this new field. Overall, the diverse imagery, compositions, atmosphere and interactive devices in the work of these artists join forces to create a seldom seen poetic flavor for this exhibition. This exhibition makes a deep impression on the minds of the audience, and such a profound experience has nothing to do with technological gimmicks, but is more inclined towards the poetic realm and associations with the humanities. Essentially, the exhibition theme, Wandering in Poetry, wasn’t predefined by a curatorial topic, but rather gradually revealed itself through the synergy created by the works as a group.

J J Shih, Director of Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts at Taipei National University of the Arts Fermenting Poetry from Technology—Preface Taiwan’s national hope of developing into tomorrow’s island of technology lies in its people’s acceptance and use of technological products, and it could be said that both technological equipment and software are considerably commonplace. Mobile phones, every household equipped with a computer, online shopping and searching for information and using email to communicate: these are just some obvious examples among many of the rampant spread of technology. Culture and the arts are even undergoing unavoidable, qualitative and quantitative change. Most obviously, with technology backing new media artists their numbers are increasing daily, as are related exhibitions. It is undeniable that technology-based art has become the unavoidable fashion of our times, but even more important than the creation of transformations in creative media and technology, is the substantial expansion in creative thinking and space for imagination created by new technologies, and also the ways we appreciate and experience art. On the international stage of contemporary art, techno art is already considered a celebrated theory and never-ending source of power, and in Taiwan, it has completely captured the attention of younger generation artists and become a creative choice in high demand. Currently, although the work of domestic technology-based artists has just begun and the numbers involved are still few, there are several Taiwanese artists who have captured the attention and received affirmation on the international stage, and this has inspired even greater numbers to join in. Looking around Taiwan, many initiatives spurring on technology-based art have taken shape. Not only are many universities offering art education courses, but they are also including techno art as a formal course of study. Additionally, studios have been established for research and development, businesses are funding foundations and the government has instituted policies that allocate grants for the creative technology industry. As early as three years ago, thanks to the support of the domestic technology industry and their identification with this project, the Techo Art Creation Project segment of the granting program at the National Culture and Arts Foundation was set forth. This all has been clearly explained; Taiwan, island of technology, has all it takes in terms of resources, talent, recognition and technology to sustain promotion and development of future forms of technology-based art, but perhaps what we require is more effective initiative and better integrated systems. Technology has gradually changed our everyday habits, as well as our values and ways of thinking. However, these aren’t necessarily all positive changes. Everyday, we see first hand and hear stories of how technology has led individuals astray and created a multitude of social problems. Truly, this we should acknowledge: there is no way possible for technology-based art to be a panacea for all art or become the sole wave of the future. Currently, the general public has confirmed that technology-based art has created numerous possibilities and opened completely new horizons, yet there are many critics who have raised warnings in succession—this spectacular wave of interactivity in techno art may gradually lead art to amusement for the masses, greatly reducing art’s ideological connotation and humanistic depth. To be fair, techno art has indeed launched a new era in artistic perception, but where the value and significance of this new era is heading remains stuck in a vast and hazy phase, abetted by the theorists’ inability to articulate comprehensive themes. In the creative camp, discourses tend to focus on new approaches for technology-based art and a return to art's essence. It cannot be denied, this is a question that every artist working with new technology must ask him or herself, and then find an answer. Considering the degree to which technology has been assimilated into the daily life of Taiwan, techno art is still a very fresh and difficult to fathom term. Therefore, Taiwan has a long way to go before it can answer Mr. Stan Shih’s call, and advance from being the island of technology to the island of cultural technology, and even take the lead as the techno art island. This year, the National Culture and Arts Foundation, with the assistance of contributions from private businesses, has awarded grants to artists working with new technology; mounted a traveling exhibition at museums in northern, central and southern Taiwan to introduce new achievements in the field of technology-based art to the public and organized a teacher training camp along with a course of techno-art related lectures. It is the hope of everyone involved that this programming, under the guidance of NCAF, will yield many possibilities for the future of the arts and provide the people of Taiwan with an enjoyable and enriching experience. This year’s honors have been bestowed upon five artists: Tsai Wan-Shuen, Chang Po-Chih, Lin Jiun-Ting, Lin Chi-Wei and Wu Chi-Tsung. Each artist uses new media differently to carefully express their individual concepts, aesthetic inclinations and interpretation of culture. The collected works of these five artists, besides exhibiting the multiple faces of technology-based art in Taiwan, also reflect the investigative attention to multiple layers of significance by local artists in this new field. Overall, the diverse imagery, compositions, atmosphere and interactive devices in the work of these artists join forces to create a seldom seen poetic flavor for this exhibition. This exhibition makes a deep impression on the minds of the audience, and such a profound experience has nothing to do with technological gimmicks, but is more inclined towards the poetic realm and associations with the humanities. Essentially, the exhibition theme, Wandering in Poetry, wasn’t predefined by a curatorial topic, but rather gradually revealed itself through the synergy created by the works as a group.

Chairman, National Culture and Arts Foundation Kuei-shien Lee Wandering in Poetry is the second instance of the National Culture and Arts Foundation’s(NCAF) exhibition Techno Art Creation Project, and presents the artwork of this year’s five awardees. From April 28 to December 23 of 2007, the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts and the Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts at Taipei National University of the Arts will host this traveling exhibition. Exhibited works include: Tsai Wan-Sheun’s Nighttime Wandering, Chang Po-Chih’s Floating, Lin Jiun-ting’s Disappearance, Lin Chi-Wei’s Kafka Machine and Wu Chi-Tsung’s Wire Mesh III. With the Techno Art Creation Project the NCAF intends to develop all aspects of the art field by actively cultivating talented domestic artists working with technology-based art, encouraging technology-based artwork and expressions, and especially facilitating this kind of programming by establishing a platform for collaboration between industry and the arts. This program allies many technology related businesses together in undertaking assistance programs, including: Taiwanese first generation technology entrepreneur Andrew Chew, and his Chew’s Culture Foundation; the Acer Foundation, which devotes itself to promoting connections between digital technology and the arts; and the Lite-On Cultural Foundation, a long term supporter of community cultural and educational programs. For their dedication to promoting the arts, I hold these organizations in my highest esteem. Additionally, VIBO Telecom Inc. supported this exhibition by promoting the techno-art education program and made it possible to attract more visitors to experience the magical and fascinating world of technology-based art. Through various aspects of this educational programming, we hope to assist teachers and students along with the general public in better understanding the principles and mysteries of technology-based art, and take a step further in inspiring creativity with digitalization. For this valuable contribution from VIBO Telecom Inc., the National Culture and Art Foundation wishes to express its sincerest gratitude. Finally, we would like to thank EPSON for support with projection equipment, ARTCO Monthly for media assistance and the team at Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts at Taipei National University of the Arts for exhibition implementation.

Chairman, National Culture and Arts Foundation Kuei-shien Lee Wandering in Poetry is the second instance of the National Culture and Arts Foundation’s(NCAF) exhibition Techno Art Creation Project, and presents the artwork of this year’s five awardees. From April 28 to December 23 of 2007, the Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts, the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts and the Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts at Taipei National University of the Arts will host this traveling exhibition. Exhibited works include: Tsai Wan-Sheun’s Nighttime Wandering, Chang Po-Chih’s Floating, Lin Jiun-ting’s Disappearance, Lin Chi-Wei’s Kafka Machine and Wu Chi-Tsung’s Wire Mesh III. With the Techno Art Creation Project the NCAF intends to develop all aspects of the art field by actively cultivating talented domestic artists working with technology-based art, encouraging technology-based artwork and expressions, and especially facilitating this kind of programming by establishing a platform for collaboration between industry and the arts. This program allies many technology related businesses together in undertaking assistance programs, including: Taiwanese first generation technology entrepreneur Andrew Chew, and his Chew’s Culture Foundation; the Acer Foundation, which devotes itself to promoting connections between digital technology and the arts; and the Lite-On Cultural Foundation, a long term supporter of community cultural and educational programs. For their dedication to promoting the arts, I hold these organizations in my highest esteem. Additionally, VIBO Telecom Inc. supported this exhibition by promoting the techno-art education program and made it possible to attract more visitors to experience the magical and fascinating world of technology-based art. Through various aspects of this educational programming, we hope to assist teachers and students along with the general public in better understanding the principles and mysteries of technology-based art, and take a step further in inspiring creativity with digitalization. For this valuable contribution from VIBO Telecom Inc., the National Culture and Art Foundation wishes to express its sincerest gratitude. Finally, we would like to thank EPSON for support with projection equipment, ARTCO Monthly for media assistance and the team at Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts at Taipei National University of the Arts for exhibition implementation.

Lee Jiun-Hsien / Director of Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts The Avant-Garde in Taiwan Since art comes from society, concepts and forms in art develop alongside social advances. When humanity discovered bronze casting, forms of statuary changed, and after World War II, the plastics industry facilitated the use of acrylics. In a similar way, digital and electro-optical technology has provided contemporary artists with a foundation for putting into practice technology based art. Technology in today’s world is all encompassing. Technology based art in Taiwan basically combines digital automation and projection equipment and some combinations of digital automation and machinery. As for forays into more cutting-edge technology, Taiwan is still in its beginning stages, and the above list essentially sums up the extent of digital technology in the arts in Taiwan. Digitizing stems from the computer; since the computer can only process digital information, conversion to digital format is the prerequisite for using a computer. At the time of the Second World War, Americans made the first computer and the digital era was born. Digitization has extended into countless other technologies, and even though we have undergone roughly sixty years of development, the end of the quest for digital technology is nowhere in sight. Digital information is just information that has to be processed before it can be used in the human realm. Digitization expands the human mind and given the assistance from the right machinery, it can even extend the reach of our limbs. Taiwan plays an important role in the global digital technology industry. As the core technologies of digitalization and programming developed, Taiwan’s contributions to the manufacture of hardware components such as scanners, notebook computers, microchips and others has been extremely significant. While the computer industry in Taiwan has focused on the production of hardware, there has been a relative lack of attention to software development. Due to this, and the high cost of prepackage software, there is still enormous room for growth in this area of technology based art in Taiwan. Technology based art relies on equipment and skill, and therefore requires more outside support, and therefore it is difficult for individual artists to make remarkable breakthroughs. From 2006, the National Culture and Arts Foundation has helped facilitate the development of new technology art in Taiwan with its support and backing, which has played a significant role in promoting Taiwan’s participation in this field. Wandering in Poetry: the 2nd NCAF Techno Art Creation Project, was made possible by the combined support of ACER, EPSON, ARTCO Monthly, VIBO Telecom Inc., Chew’s Culture Foundation, Lite-On Cultural Foundation, and other organizations. The museum would like to extend its sincerest respect and gratitude to the executive team at the Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts of Taipei National University of the Arts for their professional contribution in selecting artists Tsai Wan-Shuen, Chang Po-Chih, Lin Jiun-Ting, Lin Chi-Wei and Wu Chi-Tsung for this award. We look forward to watching these artists continue to grow and develop in this field.

Lee Jiun-Hsien / Director of Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Arts The Avant-Garde in Taiwan Since art comes from society, concepts and forms in art develop alongside social advances. When humanity discovered bronze casting, forms of statuary changed, and after World War II, the plastics industry facilitated the use of acrylics. In a similar way, digital and electro-optical technology has provided contemporary artists with a foundation for putting into practice technology based art. Technology in today’s world is all encompassing. Technology based art in Taiwan basically combines digital automation and projection equipment and some combinations of digital automation and machinery. As for forays into more cutting-edge technology, Taiwan is still in its beginning stages, and the above list essentially sums up the extent of digital technology in the arts in Taiwan. Digitizing stems from the computer; since the computer can only process digital information, conversion to digital format is the prerequisite for using a computer. At the time of the Second World War, Americans made the first computer and the digital era was born. Digitization has extended into countless other technologies, and even though we have undergone roughly sixty years of development, the end of the quest for digital technology is nowhere in sight. Digital information is just information that has to be processed before it can be used in the human realm. Digitization expands the human mind and given the assistance from the right machinery, it can even extend the reach of our limbs. Taiwan plays an important role in the global digital technology industry. As the core technologies of digitalization and programming developed, Taiwan’s contributions to the manufacture of hardware components such as scanners, notebook computers, microchips and others has been extremely significant. While the computer industry in Taiwan has focused on the production of hardware, there has been a relative lack of attention to software development. Due to this, and the high cost of prepackage software, there is still enormous room for growth in this area of technology based art in Taiwan. Technology based art relies on equipment and skill, and therefore requires more outside support, and therefore it is difficult for individual artists to make remarkable breakthroughs. From 2006, the National Culture and Arts Foundation has helped facilitate the development of new technology art in Taiwan with its support and backing, which has played a significant role in promoting Taiwan’s participation in this field. Wandering in Poetry: the 2nd NCAF Techno Art Creation Project, was made possible by the combined support of ACER, EPSON, ARTCO Monthly, VIBO Telecom Inc., Chew’s Culture Foundation, Lite-On Cultural Foundation, and other organizations. The museum would like to extend its sincerest respect and gratitude to the executive team at the Kuandu Museum of Fine Arts of Taipei National University of the Arts for their professional contribution in selecting artists Tsai Wan-Shuen, Chang Po-Chih, Lin Jiun-Ting, Lin Chi-Wei and Wu Chi-Tsung for this award. We look forward to watching these artists continue to grow and develop in this field.

Wu, Chi-Tsung 2004 Graduated from Finearts Department in Taipei National University of the Arts 1981 Born in Taipei Exhibition 2006 “Between the observer and the observed ”, 2006 Lianzhou International Photo Festival, Lianzhou, China “Hyper Design“ 6th Shanghai Biennale, Shanghai Art Museum, Shanghai, China “Taipei / Taipei”view and points, Taipei Fine Art Museum, Taipei, Taiwan “Artists at Glenfiddich”, Gallery of Glenfiddich Distillery, Scotland, UK “Infiltration ? and Visions”, Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, China 2005 “Experimenta Vanishing Point”Exhibition BlackBox, the Arts Centre, Melbourne, Australian “The Elegance of Silence”, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan “Eye Dream”Multiple Realities, Taiwan Contemporary Photography and Painting cultural center of Taiwan at Paris, Paris, France & City Hall Gallery, Ottawa, Canada, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Art, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 2004 “Tracing Self”The New Identity Part-5, Contemporary Taiwanese Art Exhibition, Artium Art Gallery, Fukuoka, Japan 2003 “City_net Asia”, Seoul Museum of Art, Korea “Simulation”--- The Poetics of Imaging in the Technology Age, Hong-Gah Museum, Taipei, Taiwan “Streams of Encounter"-Electronic Media Based Artworks, Taipei Fine Art Museum, Taipei, Taiwan Solo Exhibition 2004 Solo Exhibition, IT Park Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan Awards 2006 “Artes Mundi”, Wales International Visual Art Prize, National Museum Cardiff, Cardiff, UK 2003 “2003 Taipei Arts Award”, Taipei Fine Art Museum, Taipei, Taiwan Residency 2006 “Artists at Glenfiddich 06”The Glenfiddich Artists in Residence Programme, at Glenfiddich Distillery, Dufftown, scotland, UK “Taiwan-England Artists Fellowships Programme 2006”, at site gallery, sheffield, UK Main References Yu Wei, Illusion Laid Bare: Discussing Wu Chi-tsung’s Images, Modern Art No.124, 2006, p.14 Amy Cheng Heui-Hua, Sensibility Unveiled Wu Chi-tsung’s Work, Modern Art No.113, 2004, p.56

Wu, Chi-Tsung 2004 Graduated from Finearts Department in Taipei National University of the Arts 1981 Born in Taipei Exhibition 2006 “Between the observer and the observed ”, 2006 Lianzhou International Photo Festival, Lianzhou, China “Hyper Design“ 6th Shanghai Biennale, Shanghai Art Museum, Shanghai, China “Taipei / Taipei”view and points, Taipei Fine Art Museum, Taipei, Taiwan “Artists at Glenfiddich”, Gallery of Glenfiddich Distillery, Scotland, UK “Infiltration ? and Visions”, Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, China 2005 “Experimenta Vanishing Point”Exhibition BlackBox, the Arts Centre, Melbourne, Australian “The Elegance of Silence”, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan “Eye Dream”Multiple Realities, Taiwan Contemporary Photography and Painting cultural center of Taiwan at Paris, Paris, France & City Hall Gallery, Ottawa, Canada, Kaohsiung Museum of Fine Art, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 2004 “Tracing Self”The New Identity Part-5, Contemporary Taiwanese Art Exhibition, Artium Art Gallery, Fukuoka, Japan 2003 “City_net Asia”, Seoul Museum of Art, Korea “Simulation”--- The Poetics of Imaging in the Technology Age, Hong-Gah Museum, Taipei, Taiwan “Streams of Encounter"-Electronic Media Based Artworks, Taipei Fine Art Museum, Taipei, Taiwan Solo Exhibition 2004 Solo Exhibition, IT Park Gallery, Taipei, Taiwan Awards 2006 “Artes Mundi”, Wales International Visual Art Prize, National Museum Cardiff, Cardiff, UK 2003 “2003 Taipei Arts Award”, Taipei Fine Art Museum, Taipei, Taiwan Residency 2006 “Artists at Glenfiddich 06”The Glenfiddich Artists in Residence Programme, at Glenfiddich Distillery, Dufftown, scotland, UK “Taiwan-England Artists Fellowships Programme 2006”, at site gallery, sheffield, UK Main References Yu Wei, Illusion Laid Bare: Discussing Wu Chi-tsung’s Images, Modern Art No.124, 2006, p.14 Amy Cheng Heui-Hua, Sensibility Unveiled Wu Chi-tsung’s Work, Modern Art No.113, 2004, p.56

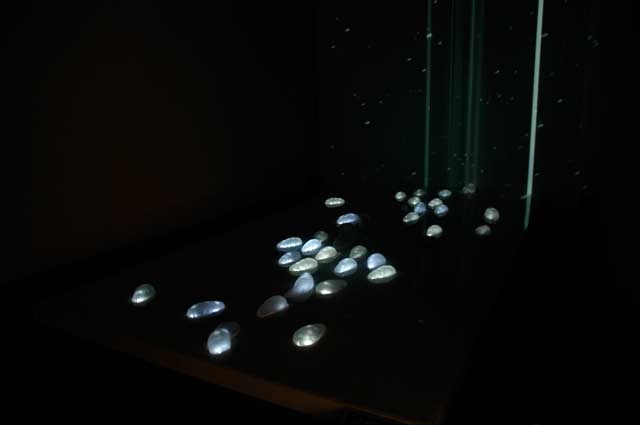

Chang, Po-Chih 1979 Born in Tainan 2003 Graduated from Finearts Department in Taipei National University of the Arts Exhibition 2006 Regulation works “Lightriver”, Exhibition “ AFTER DARK“ at Umay Building, HauShan Cultural and creative Industry Center 2005 “Wenzhou Arts Festival II”Exhibition, Taipei, Taiwan “Plankton” Exhibition, ETAT, Taipei, Taiwan 2004 “Floating”exhibition, ETAT, Taipei “失格裂縫”exhibition, the student center of National Taiwan University, Taipei Solo Exhibition 2005 “Plankton” Exhibition, ETAT, Taipei, Taiwan 2004 “Floating”exhibition, ETAT, Taipe, Taiwan Performance 2007 Live Real-time interactive performance with DMS light art at National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art 2006 Regulation works ”Plankton”,”Flower”,”Lightdance” was selected by “Weather In My Brian Sound – Visual Art Festival”, Taipei Taiwan Visual director of Opera “Der Ring Des Nibelungen”, National Chiang Kai Shek Cultural Center, Taipei, Taiwan Piece of Light Art “Lightriver” at Tai Shin Financial Tower 2005 Regulation works “Plankton” was selected by 2005 Siggraph Taipei & Computer Graphics Workshop, Taiwan Regulation works “Bit” was selected by WOCMAT(Workshop on Computer Music and Audio Technology), Taipei, Taiwan Awards 2006 Awarded by National Culture and Arts Foundation with subsidy to digital arts pieces creation

Chang, Po-Chih 1979 Born in Tainan 2003 Graduated from Finearts Department in Taipei National University of the Arts Exhibition 2006 Regulation works “Lightriver”, Exhibition “ AFTER DARK“ at Umay Building, HauShan Cultural and creative Industry Center 2005 “Wenzhou Arts Festival II”Exhibition, Taipei, Taiwan “Plankton” Exhibition, ETAT, Taipei, Taiwan 2004 “Floating”exhibition, ETAT, Taipei “失格裂縫”exhibition, the student center of National Taiwan University, Taipei Solo Exhibition 2005 “Plankton” Exhibition, ETAT, Taipei, Taiwan 2004 “Floating”exhibition, ETAT, Taipe, Taiwan Performance 2007 Live Real-time interactive performance with DMS light art at National Taiwan Museum of Fine Art 2006 Regulation works ”Plankton”,”Flower”,”Lightdance” was selected by “Weather In My Brian Sound – Visual Art Festival”, Taipei Taiwan Visual director of Opera “Der Ring Des Nibelungen”, National Chiang Kai Shek Cultural Center, Taipei, Taiwan Piece of Light Art “Lightriver” at Tai Shin Financial Tower 2005 Regulation works “Plankton” was selected by 2005 Siggraph Taipei & Computer Graphics Workshop, Taiwan Regulation works “Bit” was selected by WOCMAT(Workshop on Computer Music and Audio Technology), Taipei, Taiwan Awards 2006 Awarded by National Culture and Arts Foundation with subsidy to digital arts pieces creation

Lin, Chi-Wei 2000~2002 Residency study on the issue of Multi-media/electronic art in National Studio of Contemporary Arts in France 1994~1998 Master study of Cultural Anthropology in NIA for aboriginal/Taoism ritual music 1996 Column writer for the press "POTS" 1995 Curator of Taipei Industrial arts festival 1992 Founder of the first experimental music group in Taiwan: Zero and Sound Liberation Organization 1989 Bachelor study of French Literature 1971 Born in Taipei Exhibition 2006 Karma in Pause Mode, Solo Exposition with mixed medias, Chiwen Gallery Taipei, Taiwan Video arts “Tape Actions”, Nitrianska Gallery, Nitra, Slovakia The Last Strike of Lin ChiWei's Noise House, Taipei Fine Arts Museum Taipei, Taiwan 2005 La Tour Eiffel n'a jamais été aussi belle/Galerie Frédéric Giroux/Sound installation, Paris, France 2004 (13.mars)Let's Speak Baby Language! Reading Labyrinth, Elite bookstore, Taipei, Taiwan A Slow Anthropological Research on taiwanese old films, Sweetest Taboo film festival Leuven, Belgium (1st, juin)H.K.HighRemix, Technology Music concert, N.U.U.Cinema-Miaoli, Taiwan RADIO MOCA, MOCA Selection 2004, Taipei, Taiwan 2003 “Love Container” Sound-Light installation, Container Arts Festival, the star of sea- Kaoshung, Taiwan 2002 .WAV(capital culturel d'europe2002), space sound art, minnewater park-Brugge, Belgium Panorama-3, Le Fresnoy-Toucoing, France 2001 La jouissance obsène d’une machine parlante, Le Fresnoy Tourcoing, France 2000 Hong Kong – Berlin, Haus der Kultur der welt-Berlin, Germany 1997 Surprise Film Festival, Taichung Sogo, Taichung, Taiwan 1996 Taipei Art Fair, Taipei world trade center, Taipei, Taiwan 1995 K2-Technology Arts festival, National Institute of the Arts, Taipei, Taiwan 1993 Miniature Arts, Elite gallery, Taipei, Taiwan 1992 Bi-Expo with Wan-lin-wu, Fujen university library gallery, Taipei, Taiwan

Selected Performance 2007 Intestin Sonore, Les Voutes, Performance, Paris Intestin Sonore, Konsthall C, Performance, Stockholm 2006 Dashanzi International Festival of the Arts 2006, Noise-Performance, Pekin 2005 Night Chanting, Taipei artist village, Interactive performance, Taipei Nightland, Police station theatre Noise-Performance, Taipei Nightland, white water theatre Performance, Taipei 2004 (22,may)Redhouse Noise Machine, Taipei Sonar --- International Festival of Art+Technology, Audiencedrive concert, the Redhouse theater, Taipei, Taiwan (1st,juin)H.K.HighRemix, Technology Music concert, electronic dance music concert, N.U.U. Cinema-Miaoli, Taiwan Nuit Blanche, Noise Performance, Paris, France 2003 Chants Mecaniques, Noise Performance, Capital culturel d'europe2003, Lille, France PROBE, Noise performance, Rotterdam, Holland 2002 38ème Ruigissant, Net-performance, Grand Angle Voiron, Grenoble, France Taipei Electronic Arts Phenomena, Electronic Music, Hwua-shan Art distinct Taipei, Taiwan 2001 Sera puni, Sound performance, Glashaus, Karlsruhe, Germany SLAK, Sound "dance" theatre, Gallerie public-Paris, France Edith Room, Net-sound performance, Le Fresnoy, Tourcoing, France 2000 La domestication des auteur du bruit, electronic Music, Café Neruda, Taipei, Taiwan Höllisch Musik der Welt, electronic Music, Café Neruda, Taipei, Taiwan 1995 0-99 Actions, Noise-Action, Taipei Industrial Arts festival, Taipei 1994 Murmurs under hurricane, Noise-Action, Taipei 1993 Sweet your corrupting corp, Noise-Action Sickly Sweet Cafe 1992 Sleep with yourself, theatre, Fu-Jen university Film / Video 2002 A Slow Anthropological Research on taiwanese old films/experimental(13min) 2001 La jouissance obscène d'une Machine-Parlante/experimental(7min) 1997 Vidéo Brut/experimental(15min) 1995 K2/experimental(23min) 1993 Dog-man-Eat/documentary(55min) :City N�s= r@�oing, China. 2000 A Sparkling City, Taipei County Art and Technology Exhibition, Pinocchio, Taiwan Timeless Recording,Graduate Exhibition at the Tainan National College of the Arts, Tainan, Taiwan 1997 Exhibition of Metal Smith, Shi-Dai Gallery, Taichung, Taiwan Awards 2005 The Missed Tense

Selected Performance 2007 Intestin Sonore, Les Voutes, Performance, Paris Intestin Sonore, Konsthall C, Performance, Stockholm 2006 Dashanzi International Festival of the Arts 2006, Noise-Performance, Pekin 2005 Night Chanting, Taipei artist village, Interactive performance, Taipei Nightland, Police station theatre Noise-Performance, Taipei Nightland, white water theatre Performance, Taipei 2004 (22,may)Redhouse Noise Machine, Taipei Sonar --- International Festival of Art+Technology, Audiencedrive concert, the Redhouse theater, Taipei, Taiwan (1st,juin)H.K.HighRemix, Technology Music concert, electronic dance music concert, N.U.U. Cinema-Miaoli, Taiwan Nuit Blanche, Noise Performance, Paris, France 2003 Chants Mecaniques, Noise Performance, Capital culturel d'europe2003, Lille, France PROBE, Noise performance, Rotterdam, Holland 2002 38ème Ruigissant, Net-performance, Grand Angle Voiron, Grenoble, France Taipei Electronic Arts Phenomena, Electronic Music, Hwua-shan Art distinct Taipei, Taiwan 2001 Sera puni, Sound performance, Glashaus, Karlsruhe, Germany SLAK, Sound "dance" theatre, Gallerie public-Paris, France Edith Room, Net-sound performance, Le Fresnoy, Tourcoing, France 2000 La domestication des auteur du bruit, electronic Music, Café Neruda, Taipei, Taiwan Höllisch Musik der Welt, electronic Music, Café Neruda, Taipei, Taiwan 1995 0-99 Actions, Noise-Action, Taipei Industrial Arts festival, Taipei 1994 Murmurs under hurricane, Noise-Action, Taipei 1993 Sweet your corrupting corp, Noise-Action Sickly Sweet Cafe 1992 Sleep with yourself, theatre, Fu-Jen university Film / Video 2002 A Slow Anthropological Research on taiwanese old films/experimental(13min) 2001 La jouissance obscène d'une Machine-Parlante/experimental(7min) 1997 Vidéo Brut/experimental(15min) 1995 K2/experimental(23min) 1993 Dog-man-Eat/documentary(55min) :City N�s= r@�oing, China. 2000 A Sparkling City, Taipei County Art and Technology Exhibition, Pinocchio, Taiwan Timeless Recording,Graduate Exhibition at the Tainan National College of the Arts, Tainan, Taiwan 1997 Exhibition of Metal Smith, Shi-Dai Gallery, Taichung, Taiwan Awards 2005 The Missed Tense

Lin, Chi-Wei 2000~2002 Residency study on the issue of Multi-media/electronic art in National Studio of Contemporary Arts in France 1994~1998 Master study of Cultural Anthropology in NIA for aboriginal/Taoism ritual music 1996 Column writer for the press "POTS" 1995 Curator of Taipei Industrial arts festival 1992 Founder of the first experimental music group in Taiwan: Zero and Sound Liberation Organization 1989 Bachelor study of French Literature 1971 Born in Taipei Exhibition 2006 Karma in Pause Mode, Solo Exposition with mixed medias, Chiwen Gallery Taipei, Taiwan Video arts “Tape Actions”, Nitrianska Gallery, Nitra, Slovakia The Last Strike of Lin ChiWei's Noise House, Taipei Fine Arts Museum Taipei, Taiwan 2005 La Tour Eiffel n'a jamais été aussi belle/Galerie Frédéric Giroux/Sound installation, Paris, France 2004 (13.mars)Let's Speak Baby Language! Reading Labyrinth, Elite bookstore, Taipei, Taiwan A Slow Anthropological Research on taiwanese old films, Sweetest Taboo film festival Leuven, Belgium (1st, juin)H.K.HighRemix, Technology Music concert, N.U.U.Cinema-Miaoli, Taiwan RADIO MOCA, MOCA Selection 2004, Taipei, Taiwan 2003 “Love Container” Sound-Light installation, Container Arts Festival, the star of sea- Kaoshung, Taiwan 2002 .WAV(capital culturel d'europe2002), space sound art, minnewater park-Brugge, Belgium Panorama-3, Le Fresnoy-Toucoing, France 2001 La jouissance obsène d’une machine parlante, Le Fresnoy Tourcoing, France 2000 Hong Kong – Berlin, Haus der Kultur der welt-Berlin, Germany 1997 Surprise Film Festival, Taichung Sogo, Taichung, Taiwan 1996 Taipei Art Fair, Taipei world trade center, Taipei, Taiwan 1995 K2-Technology Arts festival, National Institute of the Arts, Taipei, Taiwan 1993 Miniature Arts, Elite gallery, Taipei, Taiwan 1992 Bi-Expo with Wan-lin-wu, Fujen university library gallery, Taipei, Taiwan

Selected Performance 2007 Intestin Sonore, Les Voutes, Performance, Paris Intestin Sonore, Konsthall C, Performance, Stockholm 2006 Dashanzi International Festival of the Arts 2006, Noise-Performance, Pekin 2005 Night Chanting, Taipei artist village, Interactive performance, Taipei Nightland, Police station theatre Noise-Performance, Taipei Nightland, white water theatre Performance, Taipei 2004 (22,may)Redhouse Noise Machine, Taipei Sonar --- International Festival of Art+Technology, Audiencedrive concert, the Redhouse theater, Taipei, Taiwan (1st,juin)H.K.HighRemix, Technology Music concert, electronic dance music concert, N.U.U. Cinema-Miaoli, Taiwan Nuit Blanche, Noise Performance, Paris, France 2003 Chants Mecaniques, Noise Performance, Capital culturel d'europe2003, Lille, France PROBE, Noise performance, Rotterdam, Holland 2002 38ème Ruigissant, Net-performance, Grand Angle Voiron, Grenoble, France Taipei Electronic Arts Phenomena, Electronic Music, Hwua-shan Art distinct Taipei, Taiwan 2001 Sera puni, Sound performance, Glashaus, Karlsruhe, Germany SLAK, Sound "dance" theatre, Gallerie public-Paris, France Edith Room, Net-sound performance, Le Fresnoy, Tourcoing, France 2000 La domestication des auteur du bruit, electronic Music, Café Neruda, Taipei, Taiwan Höllisch Musik der Welt, electronic Music, Café Neruda, Taipei, Taiwan 1995 0-99 Actions, Noise-Action, Taipei Industrial Arts festival, Taipei 1994 Murmurs under hurricane, Noise-Action, Taipei 1993 Sweet your corrupting corp, Noise-Action Sickly Sweet Cafe 1992 Sleep with yourself, theatre, Fu-Jen university Film / Video 2002 A Slow Anthropological Research on taiwanese old films/experimental(13min) 2001 La jouissance obscène d'une Machine-Parlante/experimental(7min) 1997 Vidéo Brut/experimental(15min) 1995 K2/experimental(23min) 1993 Dog-man-Eat/documentary(55min) :City N�s= r@�oing, China. 2000 A Sparkling City, Taipei County Art and Technology Exhibition, Pinocchio, Taiwan Timeless Recording,Graduate Exhibition at the Tainan National College of the Arts, Tainan, Taiwan 1997 Exhibition of Metal Smith, Shi-Dai Gallery, Taichung, Taiwan Awards 2005 The Missed Tense

Selected Performance 2007 Intestin Sonore, Les Voutes, Performance, Paris Intestin Sonore, Konsthall C, Performance, Stockholm 2006 Dashanzi International Festival of the Arts 2006, Noise-Performance, Pekin 2005 Night Chanting, Taipei artist village, Interactive performance, Taipei Nightland, Police station theatre Noise-Performance, Taipei Nightland, white water theatre Performance, Taipei 2004 (22,may)Redhouse Noise Machine, Taipei Sonar --- International Festival of Art+Technology, Audiencedrive concert, the Redhouse theater, Taipei, Taiwan (1st,juin)H.K.HighRemix, Technology Music concert, electronic dance music concert, N.U.U. Cinema-Miaoli, Taiwan Nuit Blanche, Noise Performance, Paris, France 2003 Chants Mecaniques, Noise Performance, Capital culturel d'europe2003, Lille, France PROBE, Noise performance, Rotterdam, Holland 2002 38ème Ruigissant, Net-performance, Grand Angle Voiron, Grenoble, France Taipei Electronic Arts Phenomena, Electronic Music, Hwua-shan Art distinct Taipei, Taiwan 2001 Sera puni, Sound performance, Glashaus, Karlsruhe, Germany SLAK, Sound "dance" theatre, Gallerie public-Paris, France Edith Room, Net-sound performance, Le Fresnoy, Tourcoing, France 2000 La domestication des auteur du bruit, electronic Music, Café Neruda, Taipei, Taiwan Höllisch Musik der Welt, electronic Music, Café Neruda, Taipei, Taiwan 1995 0-99 Actions, Noise-Action, Taipei Industrial Arts festival, Taipei 1994 Murmurs under hurricane, Noise-Action, Taipei 1993 Sweet your corrupting corp, Noise-Action Sickly Sweet Cafe 1992 Sleep with yourself, theatre, Fu-Jen university Film / Video 2002 A Slow Anthropological Research on taiwanese old films/experimental(13min) 2001 La jouissance obscène d'une Machine-Parlante/experimental(7min) 1997 Vidéo Brut/experimental(15min) 1995 K2/experimental(23min) 1993 Dog-man-Eat/documentary(55min) :City N�s= r@�oing, China. 2000 A Sparkling City, Taipei County Art and Technology Exhibition, Pinocchio, Taiwan Timeless Recording,Graduate Exhibition at the Tainan National College of the Arts, Tainan, Taiwan 1997 Exhibition of Metal Smith, Shi-Dai Gallery, Taichung, Taiwan Awards 2005 The Missed Tense

Lin, Jun-Ting 1970 Born in Taipei Exhibitions 2007 “Public=un+public” Bank ART Studio NYK, Yokohama, Japan “Orchid’s whisper, Floating Poetry ” 2007 International Orchid Art Festival Tech Art Exhibition, Tainan “Animanga !” Festival international EXIT, Maison des Arts., Creteil , France. 2006 Timeless Space: New Media Art Solo Exhibition, Dimensions Art Center, Beijing, China. Oriental Metaphor, LOOP alternative space, Seoul, Korea Emerging China, Arko Art Center, Seoul, Korea More than 10 Years of Art, Sino-American Asian Cultural Foundation, ChungShan Hall, Taipei, Taiwan Living Furniture, Busan Biennale 2006, Korea Entry Gate: Chinese Aesthetics of Heterogeneity, MoCA, Shanghai, China Art Taipei 2006, Dimensions Art Center, Huashan Culture Park, Taipei, China Labyrinth of the Senses Joumana Mourad, Taipei Artist Village, China Fiction@Love--Ultra New Vision in Contemporary Art, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore The 2nd China International Cartoon and Animation Festival, The Originals: Neo-Aesthetics of Animamix, Hangzhou Peace International Convention & Exhibition Center, China International Orchid Art Festival, Dreamy Garden, Beyond the Horizon Tech Art Exhibition, Tainan Orchid Plantation, Taiwan Artists’Diary: The Chapter of Spring Light, Taipei Artist Village, Taiwan 2006 Taipei Lantern Festival Art Lantern Area, Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall, Taiwan Fiction@Love-- Forever Young Land, Museum of Contemporary Art, Shanghai, China 2005 Exhibition of Future Sculpture, Hualien International Stone Sculpture Festival, Hualien Stone Sculpt

Lin, Jun-Ting 1970 Born in Taipei Exhibitions 2007 “Public=un+public” Bank ART Studio NYK, Yokohama, Japan “Orchid’s whisper, Floating Poetry ” 2007 International Orchid Art Festival Tech Art Exhibition, Tainan “Animanga !” Festival international EXIT, Maison des Arts., Creteil , France. 2006 Timeless Space: New Media Art Solo Exhibition, Dimensions Art Center, Beijing, China. Oriental Metaphor, LOOP alternative space, Seoul, Korea Emerging China, Arko Art Center, Seoul, Korea More than 10 Years of Art, Sino-American Asian Cultural Foundation, ChungShan Hall, Taipei, Taiwan Living Furniture, Busan Biennale 2006, Korea Entry Gate: Chinese Aesthetics of Heterogeneity, MoCA, Shanghai, China Art Taipei 2006, Dimensions Art Center, Huashan Culture Park, Taipei, China Labyrinth of the Senses Joumana Mourad, Taipei Artist Village, China Fiction@Love--Ultra New Vision in Contemporary Art, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore The 2nd China International Cartoon and Animation Festival, The Originals: Neo-Aesthetics of Animamix, Hangzhou Peace International Convention & Exhibition Center, China International Orchid Art Festival, Dreamy Garden, Beyond the Horizon Tech Art Exhibition, Tainan Orchid Plantation, Taiwan Artists’Diary: The Chapter of Spring Light, Taipei Artist Village, Taiwan 2006 Taipei Lantern Festival Art Lantern Area, Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall, Taiwan Fiction@Love-- Forever Young Land, Museum of Contemporary Art, Shanghai, China 2005 Exhibition of Future Sculpture, Hualien International Stone Sculpture Festival, Hualien Stone Sculpt

Tsai, Wan-Shuen 1978 born in Peng-Hu, Taiwan Exhibition 2007 “dog” Film Festival,24-27April,Dogpig Art Cafe。 Personal exhibition "Marées II", Centre Cultural Colombier and workshop in Art School, Rennes, Franc 2006 Personal exhibition "Mangeur de fil", Plume art gallery, Paris, France Video works ”Travel in distance”in Saint-Genis-Pouilly , France Collective exhibition "Ubiquitous", Taipei Artist Village, Taipei, France Collective exhibition " #3" and " #2 Dessin", Atelier 13, Valenciennes, France Personal exhibition "Cité Insomniaque", Le Tableau art gallery, Marseille, France Audio-Visual performance "Emanate", Lausanne and Geneva, Switzerland (with Yannick Dauby, Michael Northam, Hitoshi Kojo) 2005 Video "The pith of the aphrodisiac tree", in collective exhibition, La Box, Bourges, France (music by Abs.Hum) Collective exhibition "Nous faisons une exposition", ESBAT, France Master Degree in Fine arts, École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Tour, France 2004-2005 Six audiovisual performances with Yannick Dauby at : Taipei Artist Village (Taipei, Taiwan), Nuit Blanche (Paris, France), Maison des Sciences (Poitiers, France), Centre d'Art en L'Île 2003 Licence Degree in Fine arts, École Nationale d'Art de Nice (Villa Arson), France 2000 Collective exhibition "-(54.5 x 4.5 x 9)", Huashan Art District, Taipei Licence Degree in Fine arts, National Taiwan University of Art, Taiwan Geneva, Switerland), Athénor (St-Nazaire, France), Wistaria House (Taipei, Taiwan). 1999 Participation in the organization of Public Art festival, National Taiwan University of Art, Taiwan Awards 2007 Residence project in MOKS Art Center, The Republic of Estonia 2006 Collective exhibition "Chantiers d'Art", Cunlhat, France (with Yannick Dauby, 2nd prize of the concourse) Collective exhibition "'cUncert-x", Athénor, Saint-Nazaire, France (with Volume- Collectif, art-collective) First Prize of Video Art Ding-Tai, Taichung, Taiwan 2005 Performance and exhibition at Wistaria House, Taipei, Taiwan (with Yannick Dauby) 2004 Collective exhibition, "Mission Jeunes Artistes" meeting, Toulouse, France Art residency, Taipei Artist Village, Taiwan (with Yannick Dauby)

Tsai, Wan-Shuen 1978 born in Peng-Hu, Taiwan Exhibition 2007 “dog” Film Festival,24-27April,Dogpig Art Cafe。 Personal exhibition "Marées II", Centre Cultural Colombier and workshop in Art School, Rennes, Franc 2006 Personal exhibition "Mangeur de fil", Plume art gallery, Paris, France Video works ”Travel in distance”in Saint-Genis-Pouilly , France Collective exhibition "Ubiquitous", Taipei Artist Village, Taipei, France Collective exhibition " #3" and " #2 Dessin", Atelier 13, Valenciennes, France Personal exhibition "Cité Insomniaque", Le Tableau art gallery, Marseille, France Audio-Visual performance "Emanate", Lausanne and Geneva, Switzerland (with Yannick Dauby, Michael Northam, Hitoshi Kojo) 2005 Video "The pith of the aphrodisiac tree", in collective exhibition, La Box, Bourges, France (music by Abs.Hum) Collective exhibition "Nous faisons une exposition", ESBAT, France Master Degree in Fine arts, École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Tour, France 2004-2005 Six audiovisual performances with Yannick Dauby at : Taipei Artist Village (Taipei, Taiwan), Nuit Blanche (Paris, France), Maison des Sciences (Poitiers, France), Centre d'Art en L'Île 2003 Licence Degree in Fine arts, École Nationale d'Art de Nice (Villa Arson), France 2000 Collective exhibition "-(54.5 x 4.5 x 9)", Huashan Art District, Taipei Licence Degree in Fine arts, National Taiwan University of Art, Taiwan Geneva, Switerland), Athénor (St-Nazaire, France), Wistaria House (Taipei, Taiwan). 1999 Participation in the organization of Public Art festival, National Taiwan University of Art, Taiwan Awards 2007 Residence project in MOKS Art Center, The Republic of Estonia 2006 Collective exhibition "Chantiers d'Art", Cunlhat, France (with Yannick Dauby, 2nd prize of the concourse) Collective exhibition "'cUncert-x", Athénor, Saint-Nazaire, France (with Volume- Collectif, art-collective) First Prize of Video Art Ding-Tai, Taichung, Taiwan 2005 Performance and exhibition at Wistaria House, Taipei, Taiwan (with Yannick Dauby) 2004 Collective exhibition, "Mission Jeunes Artistes" meeting, Toulouse, France Art residency, Taipei Artist Village, Taiwan (with Yannick Dauby)

Wandering in the Poetry: a Micro-observation on the Tech-Art of Taiwan Yaohua Su, Director of Taipei Artist Village Contrary to the common belief that art and technology belong to two distinctly separate realms, in ancient Greek they were in fact homogenous and relating concepts. The Renaissance also witnessed a brief yet harmonious spell of fusion of these two, as can be seen in the life and work of Leonardo da Vinci. From the twentieth century onwards, as artists intended to aesthetically challenge the long-standing apartheid between art and technology, once again these two are brought onto to the same platform, not only to showcase unbridled imagination, but also to allow technology to enter our daily life. In the contexts of modern and contemporary arts, tech-art continually develops as a dynamic and inclusive concept. It is by no means a singular artistic movement; nor does it bear a clear definition. Rather, tech-art can be seen to broadly refer to any artwork delivered by means of modern technology including, but not limited to, photography, film, cross-field performance, kinetic art, video art, digital art, interactive art, cyber art, virtual reality, biological and genetic art (such as the work of Shu-Min Lin). As technology continually advances and expands its fields of application, it not only pushes the boundary of art to infinity, but also re-shapes the delicate relationships between art and technology. “Experimentation” and “rebellion” are widely considered to be the core values in the turbulent history of twentieth-century Western arts. As American new-media art critic Gene Youngblood has noted, “All art is experimental, or it isn’t art.” The extraordinary visions of these experimentalist and enlightening artists brought about revolutionary change in artistic styles. For example, English-born photographer Eadweard Muybrige successfully photographed a horse in fast motion using a series of 24 cameras – an achievement which not only cast significant influence upon Marcel Duchamp’s painting, Descending a Staircase No. 2, (1912), but also came to be regarded as the predecessor of cinema and animation. The mode of thinking characterized by classical arts was effectively dissolved as Futurism avidly celebrated machinery, technology and speed, while Dada and Fluxus vehemently interrogated traditional definitions of art. Similarly, the notion of ‘authenticity’, or ‘unique existence’ so vital to traditional definitions of art, was severely undermined by the development of means of mechanical reproduction, as was techniques of representing the truth by the proliferation of ‘simulacra’. To follow these developments, the notion of ‘time art’ was added to the vocabulary of creative practice, and the pursuit of speed and dynamics renovated the contents of artwork. The fusion of cross-field performing arts, including improvisation and impromptu, has taken contemporary artists to a new direction in their practice. In the 1960s when laser was first utilized as a medium for artistic creation, kinetic art, light sculpture, optical sciences, as well as issues to do with lights and space all breathed life into contemporary art. In around the same period of time, television became a new focus of the popular daily life. This is when the first piece of video art came into being, as the father of video art, Nam June Paik, exhibited the results at New York’s á GoGo Café only hours after he filmed the Fifth Avenue with a portable SONY video recorder. This paved the way for the development of computer art, communication art, digital art, cyber art, and even interactive art. It is worth noting here that in the early days, many a computer artist had previously trained as a computer engineer or a computer scientist. It was not until the 1980s when personal computers became popularized, and the development of computer programs for image arithmetic was approaching maturity, that a breakthrough from this pattern was made possible. Other remarkable examples include biological and genetic art. However, the spirit of ‘experimentation’ and ‘rebellion’ did not appear clear in the development of tech-art in Taiwan. Although Tsai, Wen-Ying, an artist of Chinese descendant, rose to fame in 1968 with his work of kinetic art, and Taiwan has since also garnered recognition for the prominent development of technology Industry, Taiwan did not seem to have taken full advantage of this potential double bonus, as far as tech-art is concerned. It was not until the 1980s that tech-art began to sprout in Taiwan, thanks to art galleries and museums which introduced foreign exhibitions of this kind to our art scene. Among the most notable of these pioneering exhibitions included French Video Art Exhibition (1984) and Laser Art Exhibition (1985) of Taipei Fine Arts Museum. From 1986 onwards, private art galleries also began to launch exhibitions featuring video installation, including Su-Chen Hung’s exhibition in Spring Gallery, and Yi-Fen Kuo’s works in Studio of Contemporary Arts (SOCA). What followed was a new social trend which attracted students of art academies to experiment in this field, as well as a flourish of media coverage on artistic thoughts and art projects, most notably in Lion Art Magazine and Artist Magazines. These early efforts gradually paid off in the next two decades or so, as the dawn of the new millennium saw the peaking of tech-art, which has now become the mainstream genre in the art world. A number of recent developments can be seen to demonstrate this new trend. For example, since its renovation, the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts has placed special emphasis on digital art. Museum of Contemporary Arts (MOCA), Taipei has focused its exhibitions on works of tech-art. Besides, albeit with limited means, alternative space and the renovated former deserted space, such as IT Park and SLY Art Space, have also played a significant role in sustaining positive energy in art practice, as they have been providing local artists with opportunities and spaces for exhibitions. The area of art education also came to embrace tech-art, as the 1990s saw a growing number of universities casting vital influence by establishing research and teaching programs as a long-term project to groom younger-generation artists and to further research in this field. These institutions include the Center for Art and Technology (founded in 1992) and Graduate School of Art and Technology (2002), Taipei National University of the Arts, Graduate Institute of Sound and Image Studies in Animation, Tainan National University of the Arts (1998), and other similar programs in National Taiwan University of the Arts as well as National Yulin University of Science and Technology. Further signs can be seen to indicate the society's growing recognition of tech-art, as sponsorships from both public and private sectors have been drawn to the development of tech-art in Taiwan. These funding bodies include a number of leading arts foundations which regularly hold arts awards and sponsor art-related projects, such as Acer Foundation, Yageo Foundation, Chew’s Culture Foundation, Lite-on Cultural Foundation, and National Culture and Arts Foundation. Moreover, public art projects can also be seen to adopt tech-art as the chief medium, such as Aura of Technology(科技靈光), i.e. the 2004 Taiwan Lantern Festival held in Taipei County, and the nearly NT$100 million public-art project in Nankang Software Park. Whether it is a temporary exhibition or permanent installation, tech-art has evidently expanded its territory beyond traditional art space, e.g. art museums, galleries, or alternative space, and made its mark on open social spaces such as office buildings, public squares and parks – an achievement which can be seen to mark a significant milestone in the development of tech-art in Taiwan. The winners of the NCAF Techno Art Creation Project, 2007 include Tsai, Wan-Shuen’s Promenade Nocturne (2003), Chang Buo-Chih’s A Floating Project, Lin, Jiun-Ting’s The Missed Tense / Vanished Tense, Lin, Chi-Wei’s Machine Kafka, and Wu, Chi-Tsung’s Wire III. All these five projects will become significant indicators of Taiwan's tech-art, as they provide five micro samples of the respective dimensions from which one can observe the development of tech-art in Taiwan. At a time when the development of tech-art is still going strong in a present continuous tense, and cannot be summarized in a perfect tense, it would seem inevitable that one can only adopt a micro approach in observing the dynamic development of tech art, since one cannot claim to offer an panoramic account on ecological and environmental issues. Overly Edutainment and Properly Interactive Art With a 3D tractor installed in the lantern, Lin Jiun-Ying ‘walks’ the viewers into a virtual space. Lin Chi-Wei’s Machine Kafka, on the other hand, requires the intervention of the body of a ‘real’ human being, in order to complete the act of understanding the messages conveyed by Machine Kafka. ‘Interaction’ is a method widely employed by contemporary tech-artists in their communication with the viewer. Via the interfaces of the human body and machinery, the artist sends to the viewer an invitation more delicately designed than one that traditional arts could offer. The viewer is now given the power to choose the elements of presentation as well as the viewing routes (Lev Manovich). On the other hand, a work of art is no longer a monologue of the artist. Rather, a piece of artwork is not completed until the viewer has engaged in the creative and interpretive processes, making the artwork connect with the external world and generate meanings (Marcel Duchamp). Broadly speaking, one’s spiritual understanding of artwork is itself a mental activity. In 1960’s Pop art, the artist would often demand that the viewer participated in the creative processes by way of game-play and interaction. Nevertheless, in a more sense, it was not until the late 1970s and early 1980s, when high-speed arithmetics began to be developed and the human came to interact with a computer by means of the bodily actions, that interactive art came to maturity. The emergence of interactive art can be seen to meet the demand of our time to call for democracy and to break the class boundaries, both in political and art-historical terms. It advocates that art should enter the popular lives by departing from the rigid traditional modes of perception which often came with a cultivating or domesticating connotations, and that art should prompt the viewer to spontaneous reflections by way of game-play. To be more specific, in the ‘viewing’ processes of the interactive tech-art, the ‘viewer’ is often encouraged to enter a situation in which the artist would be flaunting the state-of-the-art techniques, as though to participate in a ritual ceremony or a tribal feast. However, in the midst of such celebration, one also often encounter over-maneuver of technology or skills. As a result, the noise and excitement created by the interactive devices often overtake the artist’s feeble aesthetic intentions. As art, science, technology and entertainment share the same interests and the boundaries between them become obscure, there seems to be a union between commercialism and art, and too often art galleries are on the verge of turning into an interactive-science theme park. In other words, the ‘viewing’ of interactive art is in danger of becoming a pure act of consumption, as the progressive implications of interactive art seem no longer cared about. All five winners mentioned above may keep well clear of these negative aspects of the development. Or, as even computer games are now beginning to be considered as a form of ‘tech-art’, worries of this kind may seem unnecessary or even invalid. However, as both artistic and commercial works employ the same set of technological devices, the creator/producer of such works seems to be allowed to freely switch between the roles of an ‘artist’ and an ‘entrepreneur’. Questions of funding may come into play in the definition of ‘art’ here. More specifically, while practitioners of ‘tech-art’ enjoy the collective financial support of taxpayers in the form of awards and state-funded projects, tech-art commodities, on the other hand, are subject to commercial competitions as well as taxation. The crucial difference here would justifiably cause debates on the (re)-definitions of art. A relatively clear set of criteria should be constructed, no matter how obscure they might have been. Technology and Art … Connecting In his Wire III, Wu Chi-Tsung experiments on the speed and stability of images of the kinetic devices with an artist’s intuition. While in the end the artist manages to solve the technical problems, he also encountered, during the course of the creative processes, a number of beautiful accidents. This could be seen to demonstrate that while artistic concepts and aesthetic intentions play a significant role for a tech-artist in the creative processes, in the end it is the combination of techniques and concepts which determine the result of an artwork. There have always been hard-fought physical battles between tech-artists and the techniques/ media they employ in a working studio. (Lin, Chi-Wei, The convergence between art, science and mathematics). In this sense, it could be suggested that the complex situation an artist faces on a regular basis – that is, issues of techniques and media – may be best summarized as a confrontation between ‘artistic technology’ – a term fashioned by Soiizen Lab’s Technical Director, Jason Lee – and ‘tech-art’. The role of ‘Artistic technology’ is to provide the artist with all forms of employable devices including technology, equipment, tools, software techniques, hardware, and devices of system integration. National Culture and Arts Foundation (NCAF) are well aware of such needs. Such awareness is demonstrated right in the beginning of the Regulations of Funding for the Special Techno Art Creation Project . “Applying the concept of ‘matching funds’ which encourages cooperation between the arts and commercial sectors, NCAF hopes to strengthen the relationship between tech-artists and the private funding bodies by providing sponsorships and means of professional integration.” Commissioned by Department of Cultural Affairs, Taipei City Government, the Center for Digital Arts are also planning a training program for tech-art technical specialists. We understand that without the support of a strong team of technical specialists, tech-artists will continue to face the long-standing nightmare resulting from the grave dearth of resources in art technology. Consequently, this will continue to subject tech-artists to situations in which one has no options but to follow the routes taken by Wu, Chi-Tsung: that is, to let intuition and mistakes solve the problems as encountered. We hope that with the efforts from all parties, the realms of art and technology can soon be connected. Gazing at God’s Window As Tech-art opens it As opposed to a common impression which tends to associate tech-art with speed and dynamics, Tsai Wan-Shuen’s Night-Time Wandering (2003) and Chang Po-Chi’s A Floating Project take to the other end of the speed meter, i.e. slow, and in so doing probe into the world of the viewer’s perception. During most of the twentieth century, the dreams of ‘progress’ were largely fulfilled by the relentless pursuit of speed. However, in the last decade of the twentieth century, this mode of thinking began to be questioned, as a large number of highly developed countries throughout the world coincidently witnessed a series of movements which advocated the values of slowness, e.g. slow eating, slow living, or even slow sex. Such a reflection quickly fermented in the contemporary art scene (Lee, Yu-Ling, “Re-considerations of the meanings and values of time). It should be noted that while the presentational processes of tech-art could be slow, questions of ‘speed’ may not necessarily be at the core of the issue concerned. Rather, to rebel against the stereotypes created by speedy mechanical mass-reproduction, one often resorts most appropriately to a time-consuming, quasi-manual approach to the creative practice. As Milan Kundera has noted in his novel, Slowness, a sense of leisure and the pleasure of slowness may be key in the viewing of artwork. “A person gazing at God's windows is not bored; he is happy.” This is precisely the sort of mental states that we hope the viewers can enjoy, as they visit Wandering in the Poetry.