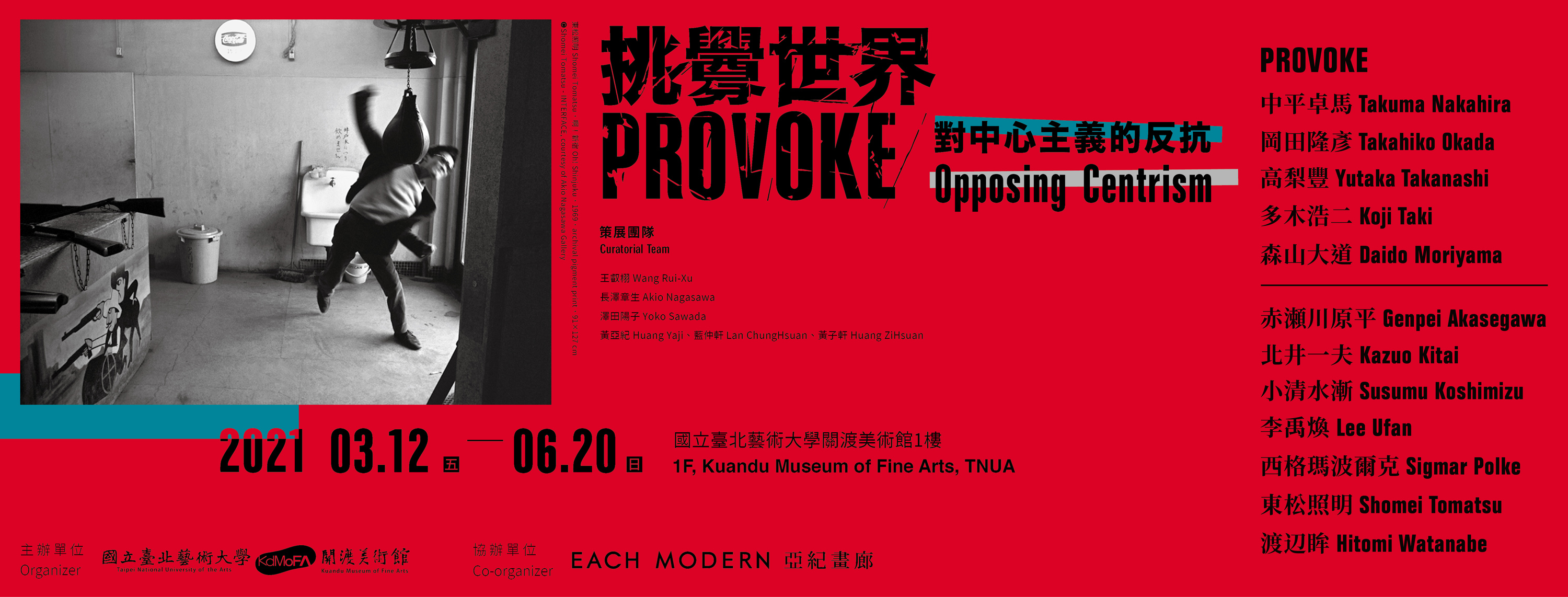

With its subtitle “provocative materials for thought”, PROVOKE advocated independent thinking, featuring photography and critical writing that sought to challenge its readers to reconsider the existing images of a politically and ideologically revolutionary time. Totaling three issues and printed in small runs of a few hundred copies each, PROVOKE stood in contrast to the collective spirit of the times; as alternatively evidenced in proliferation of “protest books” distributed in Tokyo made by anonymous student committees. These books existed in a context of disillusionment: at the end of a decade of fruitless protests and upheavals. However, unlike the documentary style of other protest books, PROVOKE members seized a subjective, fragmented, and explosive method to capture experiencing the world.

In 1969, Takuma Nakahira ended PROVOKE activities and published his own photobook “For the Language to Come”. In 1973 after releasing his critical collective “Why an Illustrated Botanical Dictionary?”, he set fire to his negatives and photographs taken during PROVOKE. Yet there still remains some very rare works: the photogravure he made for 1969 Paris Biennale – rather than gelatin silver prints, Nakahira preferred photogravure to refer the reproducibility and distributivity of posters and processions.

Daido Moriyama also focused on silkscreen at that time. He seldom produced gelatin silver prints but produced silkscreen on site as performance. From 1969 to 1972, he particularly photographed images from newspapers, advertisements, or real scenes; distinction between them was unrecognizable. Two bodies of work, “Scandalous” and “Farewell Photography”, uncovered his experiments and his relation to Pop Art.

Returning to direct photographs, there are three other photographers who indirectly contributed to PROVOKE: Shomei Tomatsu, Kazuo Kitai, and Hitomi Watanabe. Tomatsu’s major projects include photographing the U.S. occupation and subsequent Americanization of Japan, and pictures of both violence on the streets and the roaring underground of Tokyo. These visually and consciously mentored the members of PROVOKE. Kazuo Kitai, well-known for recording the life of protesters, is the earliest individual artist who published the protesters images in a very personal style. Watanabe is the most important female photographer at the time. She thoroughly photographed the student protests in both emotional and documentary way.

While PROVOKE eventually disbanded, Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, and Takuma Nakahira still played a key role in the developments of photography and avant-garde art. The discussion extended to two magazines in particular: KEN, first published in 1970 which lasted for only three issues, and DESIGN, a publication which became the core of the culture.

Mono-ha artists tended to present natural and industrial materials such as stone, soil, wood, paper, cotton, steel plates, and paraffin—things (mono)—on their own or in combination with one another. Natural matter and objects were considered not as material, but in and of themselves significant and autonomous, deviating from existing cognitions and rebelling against the values of the Western modern art.

In 1968, assisted by his friends, Nobuo Sekine constructed an earthwork titled “Phase—Mother Earth” for the first Suma Rikyu Park Contemporary Sculpture Exhibition in Kobe. These artists were all from Tama Art University, a location of student protest and lock downed. During lock down, Takuma Nakahira went to school for student activities, and later both Sekine and Nakahira met Lee Ufan. From this encounter began their interesting dialogues. In 1971, Nakahira, Lee, and Susumu Koshimizu were invited to show at Paris Biennale and spent times together. Later the year, Lee published his important writing collective “The Search for Encounter” and Nakahira designed the book. In 1970, Tokyo Biennale made a historical exhibition “Between Man and Matter” and framed Mono-ha with the commonalities of Supports/Surfaces in France, Arte Povera in Italy, and Minimalism in the United States. The Biennale catalogue used Nakahira’s work as cover: a desolating industrial land with inverting view.

Discussions revolved around questions of how to transcend Western Modernism by ending representation, a sentiment endemic to postwar Japan, a re-examination of indigenous culture as a means to bring attention to the physicality of things, and the limits of creativity: these were equivalence of PROVOKE and Mono-ha. In fact, the essential economy of gesture - a critique of hyper-productivity and the 'imagery overload' in contemporary art and society - is a constant feature throughout the careers of Lee Ufan and Susumu Koshimizu. The context in which Lee envisages his work is not limited to its immediate surroundings but encompasses the whole city. His sculptures are as much about the invisible as the visible, about the rebellion of making. Meanwhile, Koshimizu also tried to understand the real world through the surface of the object and the space of the body. All these concepts were clearly seen in Nakahira’s two large photo installation from the 1970s: “Circulation” and “Overflow”.

On the other hand, Genpei Akasegawa, an artist who emphasized the trace of Capitalism in everyday life and put forward “Capitalist Realism” published “The Red-Horse Looked at it” as a serial with Takuma Nakahira in the magazine Film Critic from July to December, 1971. The title of the series is apparently inspired by the revolutionary Russian writer Boris Savinkov’s novel The Black Horse(translated by Gendaishichosha in Japan, 1968). Both Akasegawa and Nakahira conveyed their admiration and disappointment to the revolution. Eventually, Akasegawa concluded the avant-garde art of this era by his “Hyperart Thomasson” created in 1972.