Tranquillity through windows-- Solo Exhibition of NI, Tsaichin

2011.05.06~2011.06.19

09:00 - 17:00

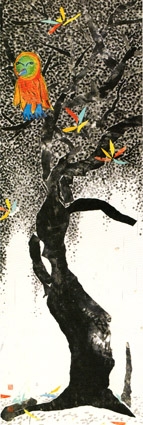

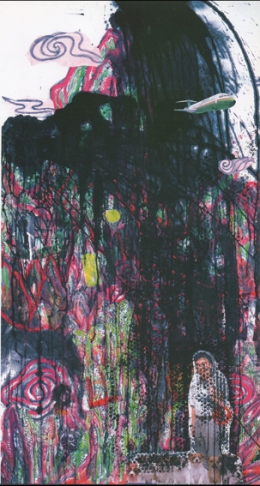

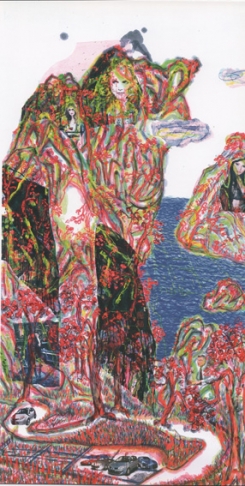

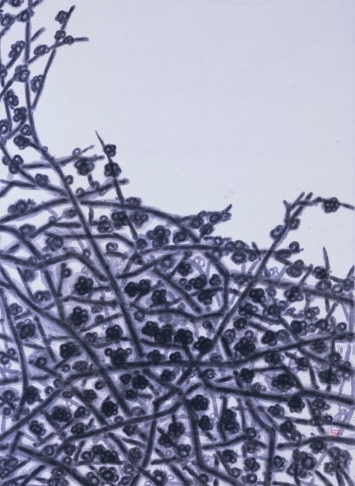

Regret and Self-Respect: Discussing the Ink Paintings of Ni Tsai-Chin (Excerpts) By: Lin Chuan-Chu I have deep impressions of Ni Tsai-Chin’s ink paintings. The earliest can be traced back to a cover of Yan-Huang Art in the early 90s, which featured a pastoral landscape painting. At the center of the painting, there is a path that winds through fields after harvest. A rich harvest of rice and scattered bundles of straw fill the fields. Mountains and the horizon are pushed extremely far and high. The whole picture has the unique bleakness of an ink painting and the astringent feel of a picture drawn with an ink pen. However, it also transcended the rules of ink paintings, and highlighted a type of physical texture and inner emotion directly revealed by a realistic sketch. Regarding Ni’s other works, his 1987 ink painting portraying a hospital ward has perhaps already played an absolute function; that is, a necessary search and appropriate use of ink paint to draw a suitable object. It is very clear that we cannot use any traditional genre of ink to depict sick beds. This seemingly plain painting foreshadows an extremely important direction: with the perspective of current developments in ink painting, Ni’s route takes him in search of talents who create breakthroughs in the ways of ink painting. These include people such as Taiwan’s Cheng Shan-Hsi, Li Mao-Cheng, Yu Peng, and Chen Ping from China. Yet, because of this foreshadowing, Ni’s ink paintings are able to stick closely to the natural qualities and scenes of the objects they portray. And, this natural object happens to be the island scenery that we all know and love. Furthermore, Ni’s more dramatic and elegant ink paintings actually solve two great problems of Taiwanese art history: after the debates surrounding ink painting and the rise of a local identity with the May Art Association, ink painting was considered an art form that was disconnected from local culture. As a result, sensitive and controversial issues regarding ethnicity were raised. His works clarify that brush and ink didn’t need to be abolished. The beauty of brush and ink existed. It had the ability to service objects in front of people’s eyes. The statement,

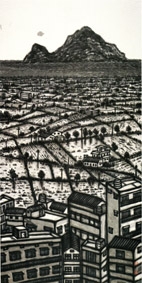

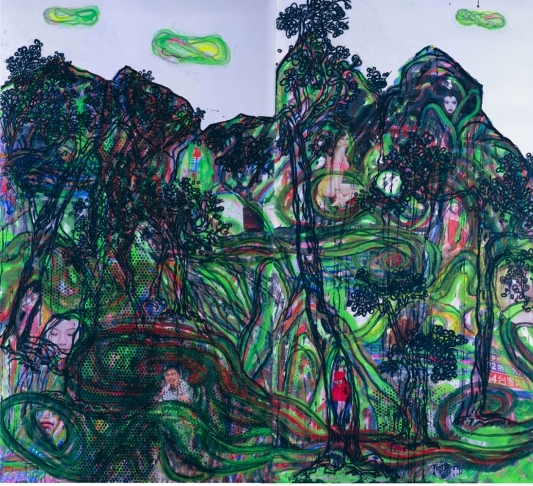

brush and ink with the times” (note 3) is not fictional; ink paintings and the local style of Taiwan can indeed coexist. Ni’s style of combining landscape painting methods with his own brush techniques reached its peak in two of his paintings, Farm Cottage by the Foot of the Mountain and Farms by the Mountain. Ni started working on these two works in 1988 and didn’t complete them until 2008. So, it wasn’t until then that we observed the pinnacle of Ni’s art. However, when looking back at Ni’s pattern of migrating and moving, he must have unrolled these scrolls to work on them a bit at a time before rolling them up to continue later. In this process, he would always recapture his initial mindset. The inextricable brush strokes found in his works must reflect this life experience. In a close viewing of the work, Farm Cottage by the Foot of the Mountain, forests painted in a traditional style can be seen on the far away mountains. However, the far away mountains in Farms by the Mountain are painted in a style that is a harmonious amalgamation of traditional ink painting and landscape painting. The traditional brush strokes slowly give way during the long process of painting. We can clearly see beautiful mountains of the serene

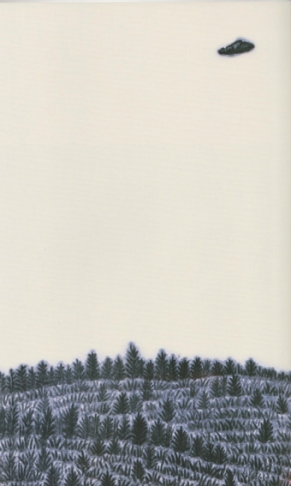

mountainous landscape of Taiwan.” A lucid image of mountains after the morning mist is presented on the rice paper. When viewing these works again in the exhibition hall, I can only say that, as a Taiwanese citizen born in Taiwan and raised on a farm, I am extremely grateful. I thank Ni for using his ink paintings to capture the fields and farms where I grew up; the corn fields and vegetable gardens that are so close to me; the tobacco house standing amongst the tobacco plants that I have come to know so well; the simple forests and lofty mountains that surround the farm I grew up on. My gratitude goes out to his clear and unreserved dedication for the land I love. When he was casted out as a second generation mainlander due to ideology differences, while simultaneously battling illness, Ni persevered without self-pity to infuse his love and soul into this land. Ni once stated that the brush and ink painters that influenced him the most are Jiang Zhao-Shen and Yu Chen-Yao. Ni’s works are layered, murky, repetitive and unitary, and not indicative of the Jiang School of painting, which emphasizes various twist and turns. However, his precise handling of composition and white space, as well as deep thoughts regarding ink painting is definitely influenced by the Jiang style. Ni’s admiration for Yu is evident in his landscape paintings, which feature scenes of vast mountains, flowing waters, and blooming flowers without people. They are in a state of self-fulfillment. After Yu’s passing in 1993, countless galleries, publishing houses, and artists began a search for a proper successor. Yet, to find a hermit with Yu’s independent, aesthetic principles and true appreciation for nature is easier said than done. To create an environment that fosters landscape painters is also easier said than done. Alas, amongst this hectic world, where can one find such a person? Is there no such person? Is there no such person?

brush and ink with the times” (note 3) is not fictional; ink paintings and the local style of Taiwan can indeed coexist. Ni’s style of combining landscape painting methods with his own brush techniques reached its peak in two of his paintings, Farm Cottage by the Foot of the Mountain and Farms by the Mountain. Ni started working on these two works in 1988 and didn’t complete them until 2008. So, it wasn’t until then that we observed the pinnacle of Ni’s art. However, when looking back at Ni’s pattern of migrating and moving, he must have unrolled these scrolls to work on them a bit at a time before rolling them up to continue later. In this process, he would always recapture his initial mindset. The inextricable brush strokes found in his works must reflect this life experience. In a close viewing of the work, Farm Cottage by the Foot of the Mountain, forests painted in a traditional style can be seen on the far away mountains. However, the far away mountains in Farms by the Mountain are painted in a style that is a harmonious amalgamation of traditional ink painting and landscape painting. The traditional brush strokes slowly give way during the long process of painting. We can clearly see beautiful mountains of the serene

mountainous landscape of Taiwan.” A lucid image of mountains after the morning mist is presented on the rice paper. When viewing these works again in the exhibition hall, I can only say that, as a Taiwanese citizen born in Taiwan and raised on a farm, I am extremely grateful. I thank Ni for using his ink paintings to capture the fields and farms where I grew up; the corn fields and vegetable gardens that are so close to me; the tobacco house standing amongst the tobacco plants that I have come to know so well; the simple forests and lofty mountains that surround the farm I grew up on. My gratitude goes out to his clear and unreserved dedication for the land I love. When he was casted out as a second generation mainlander due to ideology differences, while simultaneously battling illness, Ni persevered without self-pity to infuse his love and soul into this land. Ni once stated that the brush and ink painters that influenced him the most are Jiang Zhao-Shen and Yu Chen-Yao. Ni’s works are layered, murky, repetitive and unitary, and not indicative of the Jiang School of painting, which emphasizes various twist and turns. However, his precise handling of composition and white space, as well as deep thoughts regarding ink painting is definitely influenced by the Jiang style. Ni’s admiration for Yu is evident in his landscape paintings, which feature scenes of vast mountains, flowing waters, and blooming flowers without people. They are in a state of self-fulfillment. After Yu’s passing in 1993, countless galleries, publishing houses, and artists began a search for a proper successor. Yet, to find a hermit with Yu’s independent, aesthetic principles and true appreciation for nature is easier said than done. To create an environment that fosters landscape painters is also easier said than done. Alas, amongst this hectic world, where can one find such a person? Is there no such person? Is there no such person?

Regret and Self-Respect: Discussing the Ink Paintings of Ni Tsai-Chin (Excerpts) By: Lin Chuan-Chu I have deep impressions of Ni Tsai-Chin’s ink paintings. The earliest can be traced back to a cover of Yan-Huang Art in the early 90s, which featured a pastoral landscape painting. At the center of the painting, there is a path that winds through fields after harvest. A rich harvest of rice and scattered bundles of straw fill the fields. Mountains and the horizon are pushed extremely far and high. The whole picture has the unique bleakness of an ink painting and the astringent feel of a picture drawn with an ink pen. However, it also transcended the rules of ink paintings, and highlighted a type of physical texture and inner emotion directly revealed by a realistic sketch. Regarding Ni’s other works, his 1987 ink painting portraying a hospital ward has perhaps already played an absolute function; that is, a necessary search and appropriate use of ink paint to draw a suitable object. It is very clear that we cannot use any traditional genre of ink to depict sick beds. This seemingly plain painting foreshadows an extremely important direction: with the perspective of current developments in ink painting, Ni’s route takes him in search of talents who create breakthroughs in the ways of ink painting. These include people such as Taiwan’s Cheng Shan-Hsi, Li Mao-Cheng, Yu Peng, and Chen Ping from China. Yet, because of this foreshadowing, Ni’s ink paintings are able to stick closely to the natural qualities and scenes of the objects they portray. And, this natural object happens to be the island scenery that we all know and love. Furthermore, Ni’s more dramatic and elegant ink paintings actually solve two great problems of Taiwanese art history: after the debates surrounding ink painting and the rise of a local identity with the May Art Association, ink painting was considered an art form that was disconnected from local culture. As a result, sensitive and controversial issues regarding ethnicity were raised. His works clarify that brush and ink didn’t need to be abolished. The beauty of brush and ink existed. It had the ability to service objects in front of people’s eyes. The statement,

brush and ink with the times” (note 3) is not fictional; ink paintings and the local style of Taiwan can indeed coexist. Ni’s style of combining landscape painting methods with his own brush techniques reached its peak in two of his paintings, Farm Cottage by the Foot of the Mountain and Farms by the Mountain. Ni started working on these two works in 1988 and didn’t complete them until 2008. So, it wasn’t until then that we observed the pinnacle of Ni’s art. However, when looking back at Ni’s pattern of migrating and moving, he must have unrolled these scrolls to work on them a bit at a time before rolling them up to continue later. In this process, he would always recapture his initial mindset. The inextricable brush strokes found in his works must reflect this life experience. In a close viewing of the work, Farm Cottage by the Foot of the Mountain, forests painted in a traditional style can be seen on the far away mountains. However, the far away mountains in Farms by the Mountain are painted in a style that is a harmonious amalgamation of traditional ink painting and landscape painting. The traditional brush strokes slowly give way during the long process of painting. We can clearly see beautiful mountains of the serene

mountainous landscape of Taiwan.” A lucid image of mountains after the morning mist is presented on the rice paper. When viewing these works again in the exhibition hall, I can only say that, as a Taiwanese citizen born in Taiwan and raised on a farm, I am extremely grateful. I thank Ni for using his ink paintings to capture the fields and farms where I grew up; the corn fields and vegetable gardens that are so close to me; the tobacco house standing amongst the tobacco plants that I have come to know so well; the simple forests and lofty mountains that surround the farm I grew up on. My gratitude goes out to his clear and unreserved dedication for the land I love. When he was casted out as a second generation mainlander due to ideology differences, while simultaneously battling illness, Ni persevered without self-pity to infuse his love and soul into this land. Ni once stated that the brush and ink painters that influenced him the most are Jiang Zhao-Shen and Yu Chen-Yao. Ni’s works are layered, murky, repetitive and unitary, and not indicative of the Jiang School of painting, which emphasizes various twist and turns. However, his precise handling of composition and white space, as well as deep thoughts regarding ink painting is definitely influenced by the Jiang style. Ni’s admiration for Yu is evident in his landscape paintings, which feature scenes of vast mountains, flowing waters, and blooming flowers without people. They are in a state of self-fulfillment. After Yu’s passing in 1993, countless galleries, publishing houses, and artists began a search for a proper successor. Yet, to find a hermit with Yu’s independent, aesthetic principles and true appreciation for nature is easier said than done. To create an environment that fosters landscape painters is also easier said than done. Alas, amongst this hectic world, where can one find such a person? Is there no such person? Is there no such person?

brush and ink with the times” (note 3) is not fictional; ink paintings and the local style of Taiwan can indeed coexist. Ni’s style of combining landscape painting methods with his own brush techniques reached its peak in two of his paintings, Farm Cottage by the Foot of the Mountain and Farms by the Mountain. Ni started working on these two works in 1988 and didn’t complete them until 2008. So, it wasn’t until then that we observed the pinnacle of Ni’s art. However, when looking back at Ni’s pattern of migrating and moving, he must have unrolled these scrolls to work on them a bit at a time before rolling them up to continue later. In this process, he would always recapture his initial mindset. The inextricable brush strokes found in his works must reflect this life experience. In a close viewing of the work, Farm Cottage by the Foot of the Mountain, forests painted in a traditional style can be seen on the far away mountains. However, the far away mountains in Farms by the Mountain are painted in a style that is a harmonious amalgamation of traditional ink painting and landscape painting. The traditional brush strokes slowly give way during the long process of painting. We can clearly see beautiful mountains of the serene

mountainous landscape of Taiwan.” A lucid image of mountains after the morning mist is presented on the rice paper. When viewing these works again in the exhibition hall, I can only say that, as a Taiwanese citizen born in Taiwan and raised on a farm, I am extremely grateful. I thank Ni for using his ink paintings to capture the fields and farms where I grew up; the corn fields and vegetable gardens that are so close to me; the tobacco house standing amongst the tobacco plants that I have come to know so well; the simple forests and lofty mountains that surround the farm I grew up on. My gratitude goes out to his clear and unreserved dedication for the land I love. When he was casted out as a second generation mainlander due to ideology differences, while simultaneously battling illness, Ni persevered without self-pity to infuse his love and soul into this land. Ni once stated that the brush and ink painters that influenced him the most are Jiang Zhao-Shen and Yu Chen-Yao. Ni’s works are layered, murky, repetitive and unitary, and not indicative of the Jiang School of painting, which emphasizes various twist and turns. However, his precise handling of composition and white space, as well as deep thoughts regarding ink painting is definitely influenced by the Jiang style. Ni’s admiration for Yu is evident in his landscape paintings, which feature scenes of vast mountains, flowing waters, and blooming flowers without people. They are in a state of self-fulfillment. After Yu’s passing in 1993, countless galleries, publishing houses, and artists began a search for a proper successor. Yet, to find a hermit with Yu’s independent, aesthetic principles and true appreciation for nature is easier said than done. To create an environment that fosters landscape painters is also easier said than done. Alas, amongst this hectic world, where can one find such a person? Is there no such person? Is there no such person?

Ni Tsai-chin 1955 Born in Taipei Professor of the Department of Fine Arts, Tunghai University Professional Experiences: 1997-2000 Director of Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts 1999-2000 Visiting Scholar, the State Department.USA 2004-2007 Dean of the College of Arts, and Professor of the Department of Fine Arts, Tunghai University 2007-2008 Dean of the College of Fine Arts and Creative Design, Tunghai University

2008- Director of Taiwan Fine Arts Research Center, Tunghai University Exhibition Experiences: Selected Individual Exhibitions and Union Exhibitions: 2010 Mediaholic Art of Ni Tsai Chin, Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei 2010 Ni Tsai Chin Solo Exhibition of Scholar Painting, Show Gallery, Kaohsiung 2009 The Association of Asian Contemporary Sculptors, Gwangiu Museum of Art, Korea Ni Tsaichin Solo Exhibition, The Art Museum of China, Beijing 4P and View, Daxiang Art Space, Taichung 2008 Art Taipei 2008, Taipei World Trade Center, Taipei 2005 Place/Displace, Richmond Art Gallery Three Generations of Taiwanese Art, Pacific Asia Museum 2001 Polypolis Contemporary Arts Exhibition, Hamburg, Arts Family of Hamburg, Germany Voices Inside, Museum Italy ARTE CONTINUA Exhibition, San Gimignano, Italy 2001Water-ink Individual Exhibition, Taichung Culture Center

2008- Director of Taiwan Fine Arts Research Center, Tunghai University Exhibition Experiences: Selected Individual Exhibitions and Union Exhibitions: 2010 Mediaholic Art of Ni Tsai Chin, Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei 2010 Ni Tsai Chin Solo Exhibition of Scholar Painting, Show Gallery, Kaohsiung 2009 The Association of Asian Contemporary Sculptors, Gwangiu Museum of Art, Korea Ni Tsaichin Solo Exhibition, The Art Museum of China, Beijing 4P and View, Daxiang Art Space, Taichung 2008 Art Taipei 2008, Taipei World Trade Center, Taipei 2005 Place/Displace, Richmond Art Gallery Three Generations of Taiwanese Art, Pacific Asia Museum 2001 Polypolis Contemporary Arts Exhibition, Hamburg, Arts Family of Hamburg, Germany Voices Inside, Museum Italy ARTE CONTINUA Exhibition, San Gimignano, Italy 2001Water-ink Individual Exhibition, Taichung Culture Center

Ni Tsai-chin 1955 Born in Taipei Professor of the Department of Fine Arts, Tunghai University Professional Experiences: 1997-2000 Director of Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts 1999-2000 Visiting Scholar, the State Department.USA 2004-2007 Dean of the College of Arts, and Professor of the Department of Fine Arts, Tunghai University 2007-2008 Dean of the College of Fine Arts and Creative Design, Tunghai University

2008- Director of Taiwan Fine Arts Research Center, Tunghai University Exhibition Experiences: Selected Individual Exhibitions and Union Exhibitions: 2010 Mediaholic Art of Ni Tsai Chin, Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei 2010 Ni Tsai Chin Solo Exhibition of Scholar Painting, Show Gallery, Kaohsiung 2009 The Association of Asian Contemporary Sculptors, Gwangiu Museum of Art, Korea Ni Tsaichin Solo Exhibition, The Art Museum of China, Beijing 4P and View, Daxiang Art Space, Taichung 2008 Art Taipei 2008, Taipei World Trade Center, Taipei 2005 Place/Displace, Richmond Art Gallery Three Generations of Taiwanese Art, Pacific Asia Museum 2001 Polypolis Contemporary Arts Exhibition, Hamburg, Arts Family of Hamburg, Germany Voices Inside, Museum Italy ARTE CONTINUA Exhibition, San Gimignano, Italy 2001Water-ink Individual Exhibition, Taichung Culture Center

2008- Director of Taiwan Fine Arts Research Center, Tunghai University Exhibition Experiences: Selected Individual Exhibitions and Union Exhibitions: 2010 Mediaholic Art of Ni Tsai Chin, Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei 2010 Ni Tsai Chin Solo Exhibition of Scholar Painting, Show Gallery, Kaohsiung 2009 The Association of Asian Contemporary Sculptors, Gwangiu Museum of Art, Korea Ni Tsaichin Solo Exhibition, The Art Museum of China, Beijing 4P and View, Daxiang Art Space, Taichung 2008 Art Taipei 2008, Taipei World Trade Center, Taipei 2005 Place/Displace, Richmond Art Gallery Three Generations of Taiwanese Art, Pacific Asia Museum 2001 Polypolis Contemporary Arts Exhibition, Hamburg, Arts Family of Hamburg, Germany Voices Inside, Museum Italy ARTE CONTINUA Exhibition, San Gimignano, Italy 2001Water-ink Individual Exhibition, Taichung Culture Center